I was still unreliable, but if sufficed for labor

Stáhnout obrázek

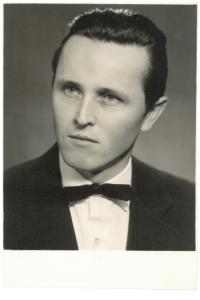

Radislav Wagner has a profound life story depicting constant conflict with the communist totality. He was born on March 15, 1932 in Southern Moravia in family of a dentist. Yet as a young boy he had to witness terrible events, when during the passage of liberating Soviet troops, his mother in a late stage of pregnancy became a victim of sexual assault. His antipathy towards the communist regime showed in his emigration attempt when being only 17 years old. Ever since the half-year imprisonment for his deed, he has been stigmatized as the system‘s enemy. After a small conflict with his superior at work, who was the Party‘s member, Radislav was condemned to spend one year in Jáchymov mines. Shortly after serving this sentence, he had to say goodbye to his closest ones again, when he had to leave for 29 months of military service in Auxiliary Technical Battalions (PTP). Yet after the release he settled down and worked at various positions in engineering plant Piesok near Brezno. Despite the exhausting work and forbearing all potential conflicts, he was considered unreliable until the end of existence of the socialist system.