“Live by the sword, die by the sword.”

Stáhnout obrázek

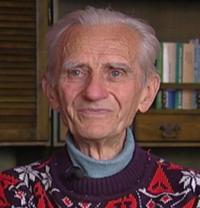

Gabriel Novák was born on July 1, 1930, in Trebišov in the family of a clerk. His father worked at the Local National Committee (MNV) as a cashier. Gabriel was raised in accordance with the principles of Christianity; his father even played the pipe organ in local Roman-Catholic church. When he finished his five-year study at the public school, in 1941 he enrolled at the Grammar school in Michalovce. He had studied there for seven years but then he was dismissed because of the distribution of leaflets aimed to fight against the people‘s democratic republic. At the same time, he was also suspected of an attempt to flee abroad, to hostile territory. Considering that he was dismissed from all secondary schools in the republic, he couldn‘t receive higher education. In June 1950 he started to work in the State Tractor Station as a tractor-driver; however, two months later he became a planner. Meanwhile he accepted an offer to join the White Legion group and subsequently on July 11, 1951, he was arrested by the state authorities. In the following year he was sentenced for anti-state activities to 22 years of imprisonment. After the trial, Gabriel Novák was transported to Ilava prison where he was present at the division of prisoners into several groups. While being in the prison, he had to take sick leave (because he had nephritis and high blood pressure) and he got to the military hospital in Mírov from where he was transported to Leopoldov prison in 1957. He was released from prison in 1962 when the amnesty was proclaimed. Though he was initially sentenced to twenty years, he spent in prison 10 years and 10 months. After the year 1989 he became involved in political life and joined the Christian Democratic Movement (KDH). He was even the cofounder of its club.