All through my childhood, I had the feeling that the war wasn‘t over

Stáhnout obrázek

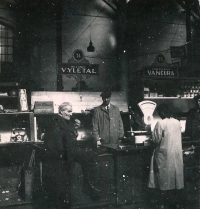

Vlasta Wernerová was born in Prague on 20 January 1943. The family lived in Old Town Square. She remembers how the People‘s Militia closed off Old Town Square so that a rally could be held in support of the incoming communist regime, and refused to let her, her mother and sister go home. She says this caused her dissenting stance against the incoming communist regime. In the first half of the 1950s, her father‘s shop was nationalised and he worked as a labourer in Aero Vysočany until he contracted tuberculosis and was forced to retire on disability. Getting into high school was difficult, and the regime did not allow her to study to be a nurse. She graduated from a high school of economics, then worked in administration all her life. She did not get into the university of economics. In the summer of 1968 she signed the Two Thousand Words manifesto and enjoyed the thaw associated with the Prague Spring, which was interrupted by the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops. She met soldiers everywhere in Prague, had to walk to work because the public transport did not run, shops were closed and fear reigned again in society. In 1970, she underwent a background check where she stated that she was not yet sure of the developments in society. Shortly afterwards she married and had a daughter. She and her husband lived in Ústí nad Labem until 1980, but their daughter was constantly ill because of the bad air. She moved back to Prague where she started working at the Research Institute of Civil Engineering. Through friends she got into transcribing samizdat literature, specifically Snář by Ludvík Vaculík. In the summer of 1989 she signed the Several Sentences petition and watched the student strikes and demonstrations with hope. In November 1989, their company engaged in a general strike, trying to dismiss the director. She was genuinely happy that the regime had finally collapsed. She was living in Prague in 2023.