I don‘t like movies that describe communism as a joke.

Stáhnout obrázek

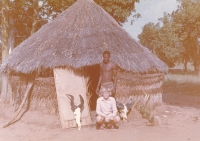

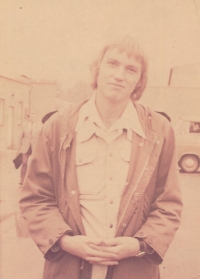

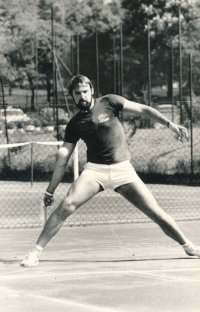

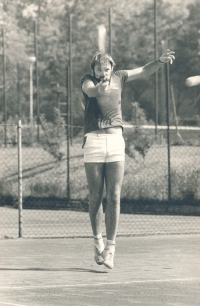

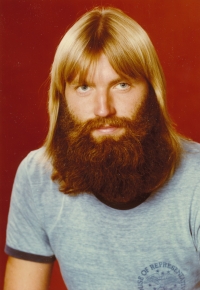

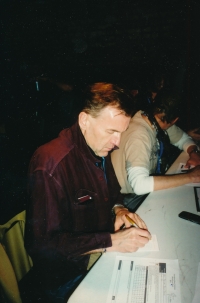

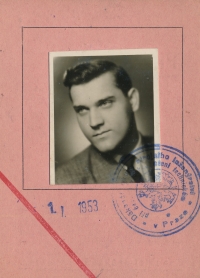

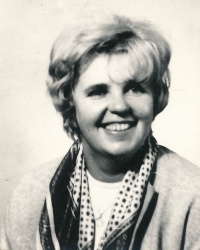

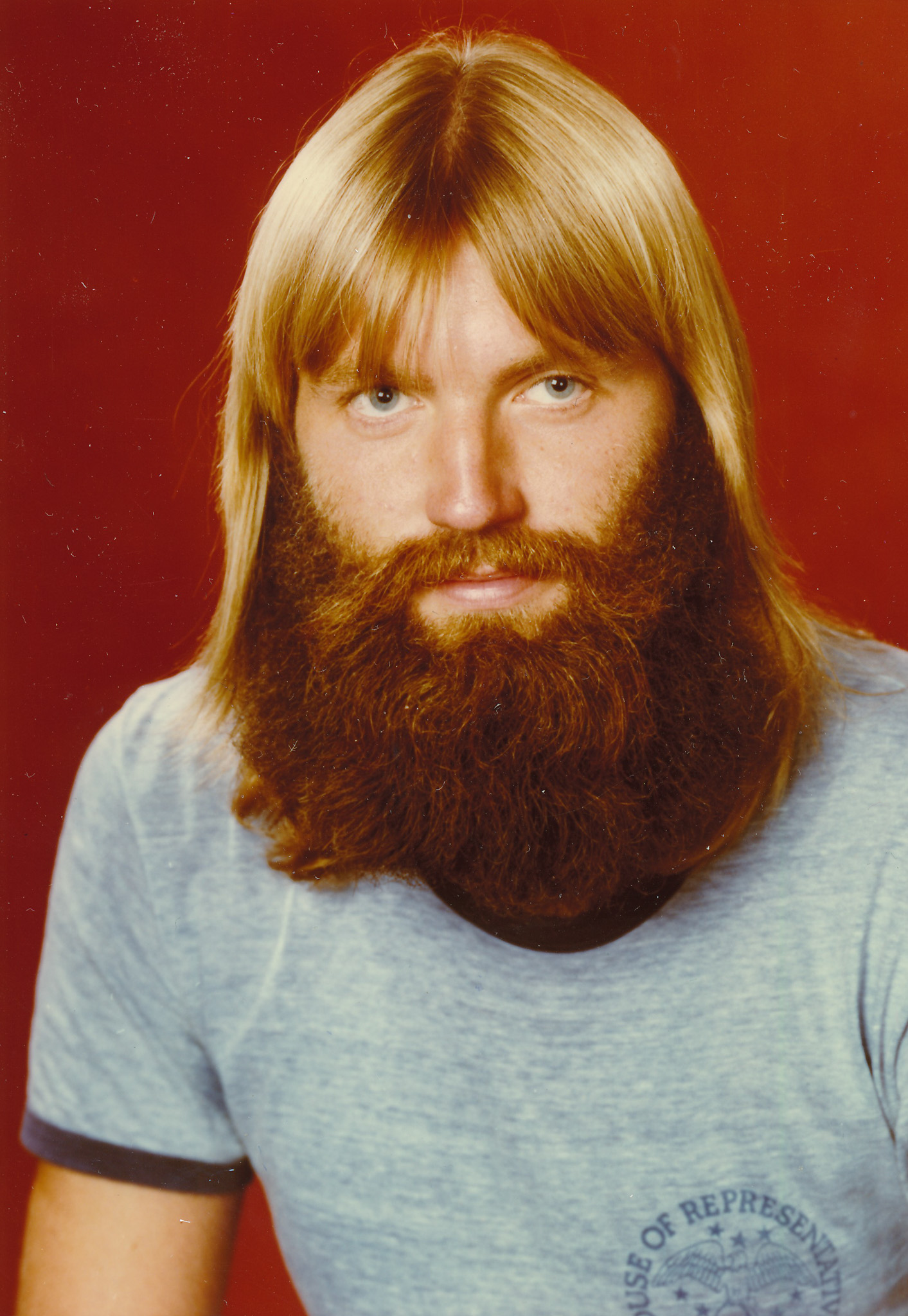

Tomáš Vydra was born on 23 February 1960 in Prague. His grandmother Ludmila Vydrová‘s brother was Václav Novák, in whose apartment the wounded Jan Kubiš hid immediately after the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich. The Novák family perished in Mauthausen; the witness‘s grandmother was saved from arrest by a brave gendarme in Nebuzele, who concealed her relationship to the Nováks from the Gestapo. Tomáš Vydra lived from 1969 to 1973 in Ghana, where his father Emil Vydra lectured at the University of Kumasi. When his contract from Polytechna expired, his father decided to remain in exile and got a job in Holland. However, Tomáš wanted to return to Czechoslovakia for his grandparents at any cost. Upon his return in June 1973, the whole family ended up in pre-trial detention, from which they were released just before Christmas. The six months in detention scarred the then thirteen-year-old Tomáš so much that he became a lifelong rebel. He refused to study, collected music by Western artists and went to illegal record sales on Sundays. Besides music, his great passion was tennis, which he eventually took up professionally. As coach of Sparta, on 25 and 26 November 1989 he allowed Václav Havel and his friends and associates into the stadium‘s interior, so that they could prepare in peace for the demonstrations on Letná Plain. At the beginning of the 1990s, he began broadcasting the programme Staré poledne on Radio 1, where he introduced listeners to music that was not allowed to be listened to under the communists, but which no one listens to anymore. At the time of the filming (2024) he was living in Prague and was still active in tennis and broadcasting his music show.