If more than one „mánička“ (a longhair man) gathered somewhere, we were always kicked out

Stáhnout obrázek

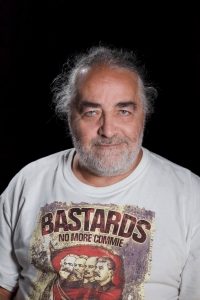

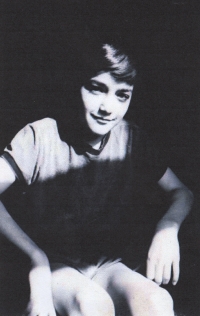

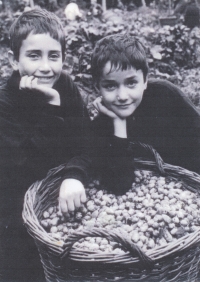

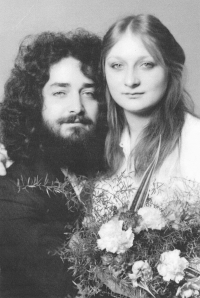

Vladimír Valeš was born on 1 March 1958 in Ústí nad Labem. His mother Angelina Babajevová came from Azerbaijan, she met his father Miroslav Valeš at the university in Moscow. Shortly after Vladimír‘s birth, the family moved to Teplice, where he lived through 1968. At the industrial high school in Kadaň he met boys from Žatec. The regime of that time classified them as troublesome youth. He did not finish school and graduated from the construction school in Děčín. In 1984 he moved to Žatec and became involved in local culture. He founded the Cultural Forum during the revolutionary events, and read a student statement at a film club screening in the Moscow cinema in Žatec. In the early 1990s, he and his friends painted a tank that stood in Žatec as a reminder of the Red Army pink. He took part in popularizing the hop-growing history of the region and became the director of the Hop Museum in Žatec. He was the head of the steering group for the UNESCO inscription of the hop-growing landscape and the town of Žatec. The proposal was successful for the second time, and on 18 September 2023 Žatec was inscribed on the World Heritage List. In 2023, Vladimír Valeš lived in Žatec.