You shouldn’t wallow in your past, you should learn something from it

Stáhnout obrázek

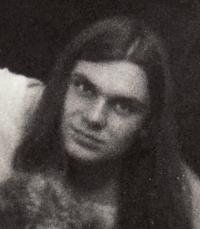

Jiří Fiedor was born on 25 September 1965 in Frýdek-Místek. For the first four years of his life he grew up with his grandmother; he moved to his parents in Třinec in 1969. He started listening to big beat as a child and grew long hair, much to the chagrin of local Communist functionaries. In 1980, aged fifteen, he moved to Prague to study at the secondary technical school operating under ČKD, where he trained as a mechanic of high-voltage devices; many of his long-haired friends from Třinec attended the same school. He attended big beat concerts and alternative („underground“) music festivals. In 1981 his school adopted stricter rules, and as he refused to have his hair shortened, he was forced to leave. He muddle along, barely scraping a living, and was given a suspended sentence for „parasitism“. After returning to Třinec he worked as a bricklayer‘s assistant and dispensed food at a hospital in Ostrava. In 1988 he started communicating more with political dissidents and distributed samizdat. In late 1988 he signed Charter 77 and helped publish the magazine Severomoravská pasivita (North Moravian Passivity). After 1989 he did journalism and documentary work, he recorded documents for Czech Television and Czech Radio. In the years 1990-1992 he was a deputy to the Czech National Council for the Civic Forum. In 2006 he established a publishing house called Pulchra. He lives in Prague.