Don‘t talk so you don‘t have to lie

Stáhnout obrázek

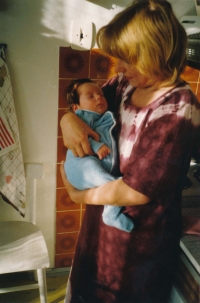

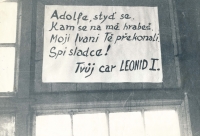

Ljuba Václavová was born on 19 May 1941 in Prague into the family of Václav Černý, a doctor, and Ida Černá, a fashion designer. Her father was active in the anti-Nazi resistance organization Jindra during the war and was chosen to treat the wounded and cold assassins hidden in the crypt of the Church of St. Cyril and Methodius in Resslova Street in Prague. He was not arrested during the Heydrichiad only because the trace died together with MUDr. Břetislav Lyčka, who shot himself just before being arrested by the Gestapo. Ljuba‘s mother was a well-known Prague fashionista who dressed stars of the silver screen such as Adina Mandlová, Lída Baarová and Věra Ferbasová in her salon. In elementary school, Ljuba Václavová encountered the regime‘s arbitrary punishment of the children of tradesmen. To help them get into their dream schools, Ljuba Václavová and several other prime ministers founded a local cell of the Czechoslovak Youth Union (ČSM) - so that the children could write their own reports. After one year at the grammar school, she transferred to the Prague Conservatory, where she studied opera singing. There she met her future husband Jiří and in 1961 they both joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) - convinced that they would dismantle the regime from within. Disillusionment came soon after, the Communists held the reins tightly in their hands and it was impossible to leave the party voluntarily. In the end, both allowed themselves to be dismissed, which later harmed them and their children during the normalization period that followed the invasion of Warsaw Pact troops on August 21, 1968. Ljuba Václavová has regretted her party membership throughout her life. Although she longed to study opera directing at university, she never applied for moral reasons—as a party member. In the 1960s, she worked for Czechoslovak Television, but during normalization, due to her poor political profile, she was forced into professional obscurity, taking only menial jobs on a contract basis without formal employment. During the Charter 77 period, she met leading Prague dissidents and became involved in samizdat publishing. Her three children—Petr, Táňa, and Veronika—faced difficulties gaining admission to universities. Ljuba Václavová only established herself professionally after the Velvet Revolution when she began working as a documentary filmmaker, dramaturge, and screenwriter, focusing on humanitarian and social themes. She also made documentaries about the children of Božena Němcová, Jiří Trnka, and the wife of poet Jan Zahradníček, who was imprisoned by the regime. Her most heartfelt and significant subject has been abandoned children. At the time of the interview in 2024, Ljuba Václavová was living in Prague.