The secret police came to the exhibition and confiscated my photographs

Stáhnout obrázek

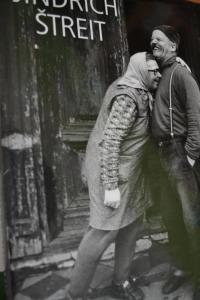

Jindřich Štreit was born September 5, 1946 in Vsetín. He grew up in Střítež in the Moravian Walachia region where his father worked as a teacher. In 1956, Jindřich‘s father was penalized by being transferred to the small village Těchanov in the Bruntál district and the family moved there. Jindřich Štreit graduated from the grammar school in Rýmařov and then from the Pedagogical Faculty of Palacký University in Olomouc, where he majored in primary school education and arts education. He worked as a teacher at a school in Rýmařov and later as a principal at schools in Sovinec and Jiříkov. He became interested in photography while he was a university student and he was photographing life in the village and exhibiting his works. Jindřich was arrested by the Security Police in 1982 for his documentary photographs and he was detained in the prison in Prague-Ruzyně for four months. The district court in Prague 7 sentenced him to conditional sentence of imprisonment for ten months with a trial period of two years for the criminal offence of defamation of the republic and the head of state. He was not allowed to continue working as a teacher and after the court verdict he also got fired from his job in the District Pedagogical Library in Bruntál. Jindřich found employment as a dispatcher at the State Farm in Ryžoviště where he then continued working until 1990. The communist regime forbade him to publish and exhibit his works. Only after the Velvet Revolution he became allowed to work publicly, travel, hold exhibitions in the Czech Republic and abroad and publish books. In 1990-2003 he lectured at the Department of Photography of Film and Television Faculty of the Academy of Music and Drama in Prague. From 1991 until 1994 he worked as an external teacher at the Department of Visual Media of the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava. From 1991 he has been teaching at the Institute of Creative Photography of the Faculty of Arts and Nature Sciences of the Silesian University in Opava.