„We definitely saw something that I hope mankind will not and should not see for a long time to come… You know, it has left its mark on each and every one of us in a way. To see so many corpses – you don’t get to see that normally.”

Stáhnout obrázek

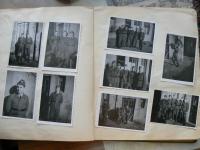

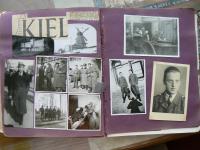

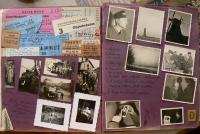

Mr. Česlav Roubíček was born in 1923 in Lysé nad Labem. In July 1942 he passed the state leaving exam at a grammar school in Prague. A few months after his exam, he was assigned to a forced labor unit that was about to leave for Hamburg. The transport left at the beginning of October 1942. In Hamburg the slave laborers were given fire-fighters‘ uniforms and were transported to the port of Kiel, where they took part in a training. They were employed in the category Zwangsarbeiter - slave laborers. Česlav Roubíček was trained for the so-called Luftschutz - anti-aircraft defense. Their main tasks included extinguishing fires of buildings and the disposing of debris and victims of air raids. Mr. Roubíček was in Germany until August 1943, when his group was replaced by a transport of further young men. After his return to the Protectorate he worked as an assistant worker in the steelworks Kladno and later in the railway works in Nymburk. He personally took part in the Prague uprising of May 1945. He fought at the Vršovice train station.