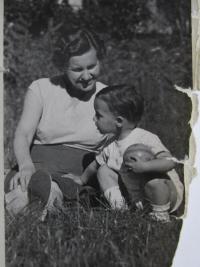

"It was like a nightmare, to be there, behind the walls, whether it was a monastery or what a building. I think it was the only multi-storey building in Marianka. Well, we were there for a few days, until one, one afternoon, or early evening it was. Because the camp was guarded by the nazis, german soldiers, from seven in the morning until seven in the evening, and in the evening, at seven o'clock in the evening they were replaced by our slovak boys, members of the Hlinka Guard's emergency units. Well, and my mom talked to one of them about the fact that I had some money sewn in the collar, that my cousin, my mother was talking, my cousin, your aunt Róžika, sewed you some money there, I don't know how much. And the slovak soldier said that yes, of course, I have a knife in my pocket. He ripped open the collar of my shirt, found money there, and immediately called his friends that they were going to the barrelhouse for a tumbler. And when the gate was abandoned, my mother went out. She went down to the woods, waiting to see if anyone was going to shoot or not, and she managed to escape from the camp. Already in the evening at dusk, after seven o'clock in the evening, she knocked on the door of our friends, Mr. Havel and his wife, who were childless partners and were in friendship, and they lived on Pražská street, so my mother crossed the forest with me on her hands, in the darkness, at night, those thirteen kilometers, or how much it is, and they accepted us together, very nicely. And when they couldn't hide us, Mr. Havel, who was the chief waiter at Carlton, and always knew, almost, almost always, heard from the Germans sitting there drinking a wine, where they would be raiding, or whether they would be raiding in that neighborhood, in which we lived on Pražská street or whether they will be in Lamač where his sister lived, or in Devínska Nová Ves, where his grandmother lived, that is, according to that, grandmother, the mother of Mr. Ondrej Havel. Well, we always alternated these three locations, either we were hiding in Pražská or Devínska Nová Ves, or in Lamač.”