“Home was very, very close already. We already had a small flag in the tank that we wanted to plant into Czechoslovak soil. But almost all tanks were eliminated. Maybe as few as one tank remained…”

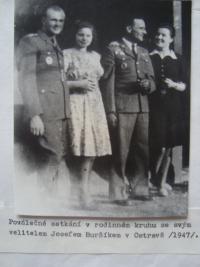

Vladimír Palička was born 27.1.1923 in Zdolbunov, Volhynia. His grandparents came to Volhynia in the middle of the nineteenth century in search of better life. His father was in the Czechoslovak legions and after the war he worked in the railway depot. Before the war started Mr. Palička attended a Polish and a Czech elementary school. He then started to study an engineering school but couldn‘t finish it due to the arrival of the Germans. In 1942 - 1944 he worked as a locomotive serviceman. In 1942 he started to work for the resistance movement; he cooperated with a guerilla group that he supplied with information regarding the movement and the cargo of train convoys. His activities are described in the book What the railroad rang for (it appeared in Polish only). In 1944 he joined the Czechoslovak army and was assigned to the tank corps. He fought in battles at Dukla and in Silesia. He was driving an armored vehicle for a couple of days. Then he was assigned the task of training Silesian volunteers in Albertov. After the war Mr. Palička stayed in the army. He accomplished a school in the Soviet Union and he did distance learning at the Military Academy in Brno. He most often held pedagogical positions. For example, he taught at the military training center in Vyškov, at the Military Faculty of the Charles University and at the Higher School of tank officers in Doksy. He was also employed in the Tank Research Institute in Doksy. In the present he is actively involved in many associations that are related to the Second World War. He devotes most of his time to Czechoslovak Community of Legionaries. He died on 14th of December 2012 in Prague.