We had all the cons, there were plenty of reasons to hate us

Stáhnout obrázek

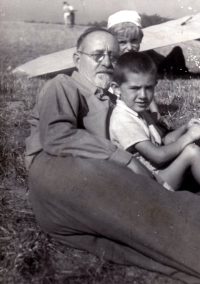

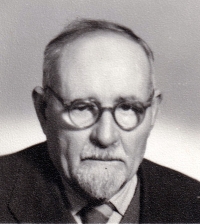

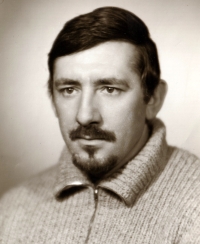

Daniel Malyk was born on January 1, 1943 in Chelm, a city located in the then war-torn western Ukraine (today Chelm is part of Poland). His father, Eugen Malyk, was a natural scientist and university professor who emigrated to Czechoslovakia shortly after World War I and probably fled back to Ukraine in 1938 to escape the Nazis. Sometime towards the end of 1944, the Nazis transported Daniel Malyk‘s entire family to the labour camp at Guntramsdorf near Vienna, one of the branch camps of the Mauthausen concentration camp. Daniel Malyk has childhood memories of the harsh conditions in the camp, recalls the bombing that completely destroyed the camp, and vividly recalls images of the last days of the war around Vienna. Thanks to his father‘s Czechoslovak citizenship, which he had acquired before the war, the family was repatriated to Czechoslovakia. They found accommodation in Komořany, which is now part of Prague 12. The inhabitants of this district lived through the dramatic days at the end of the war, when SS troops shot several dozen men defending the southern border of the capital. Daniel and his brother, two years younger than him, had to earn respect among their peers in the socially and ethnically diverse population of post-war Komořany. He graduated from the building industry and from the Czech Technical University. By the time he completed his compulsory military service, the so-called Caribbean Crisis had erupted and was in real danger of escalating into a war between East and West. Professionally, he devoted his whole life to construction, together with his wife they raised two daughters. In 2024 he lived in Prague.