I still believe times will get better

Stáhnout obrázek

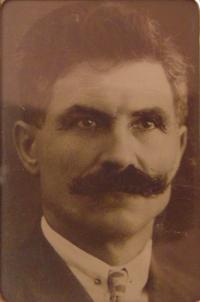

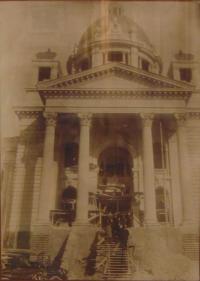

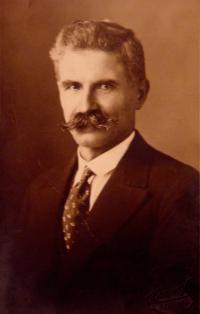

Jarmila Laník was born on 7 April 1940 in Belgrade in the then Yugoslavia. Her ancestors ran a construction business. She started going to a Czech school in 1947. Then she graduated from a high school but did not finish the law school. Following the rift between Stalin and Tito in 1948 the contact with the original motherland was cut; the witness‘ father‘s mill got confiscated and he was imprisoned. The family lost its Czechoslovak nationality and did not gain a full-fledged Yugoslav citizenship until 1961. That was also when Jarmila became a flight attendant - she is one of the first generation of flight attendants in Yugoslavia. She worked with JAT and often went to Czechoslovakia on business after 1965. She remembers the life of the Czech community in Yugoslavia. She retired in 1993 and lived in the Czech Republic for a few years. She witnessed the bombing of the former Yugoslavia in 1999 from Prague and returned to Belgrade later. Her son lives in Prague.