To say everything the way I actually mean it, so others know what kind of person I really am

Stáhnout obrázek

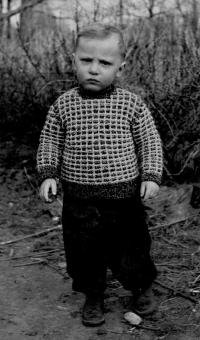

Pavel Koutenský was born on 21 January 1944 in Nové Město na Moravě. His mother died when he was ten years old. From then on his father provided all care for the house and his two sons by himself. Seeing that the family could not afford greater expenses, after grammar school Pavel decided to join the army as a full-time soldier. He became a Communist at the same time. During Prague Spring 1968 he openly expressed his support of the new political direction. After the occupation in August 1968 he was stood before a military court and convicted of offending the dignity of the republic and its representatives. This was followed by dismissal from the army and expulsion from the Party in the 1970s. The witness was then employed as a manual labourer. He remained under State Security surveillance until the Velvet Revolution.