We should have asked more questions

Stáhnout obrázek

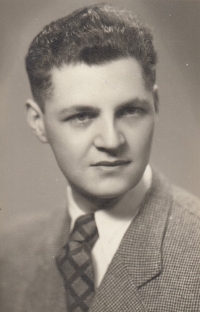

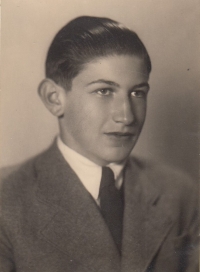

Hana Lea Kende was born on 21 May 1948 in Prague as Hana Kendeová. Her parents, Viktor Kende and Irena Kendeová, née Stadlerová, natives of České Budějovice, came from Jewish families and were deported to Terezín in April 1942. Her mother was employed there as a child educator, while her father became the head of the transport department. At the time of the family transports to the east, the parents decided to marry in order to form their own family and not be separated in the eventual transport. They were finally liberated in Terezín. Their parents, siblings and most of their other relatives perished after the transport to the Polish extermination camps, with the exception of their father‘s cousin Rudolf Kende, a gifted Czech pianist and composer, who was the only one of the family to survive despite his congenital physical disability. His mother‘s younger brother Rudolf Stadler was the founder of the magazine Klepy of the Jewish youth of České Budějovice, and was murdered by the Nazis in the spring of 1945. The complete edition of Klepy was kept by his mother Irena in her apartment until the 1990s; after the death of their parents, the Kende siblings lent the original edition to the Jewish Museum in Prague, which made it available to the public on its website. Hana grew up with her younger brother Jiří in Prague, graduated from the Nad Štolou Gymnasium and completed two years of social anthropology at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University. After the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968, she decided to stay in the UK. She studied at the University of Sussex and worked in an academic bookshop. In 2024, Hana Kende was living in Bath, England.