At least I’ll be my own master, and doubt anyone would take my spade

Stáhnout obrázek

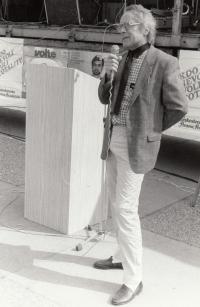

Petr Kadaník was born on 19 September 1943 in Náchod. He attended grammar school in Trutnov and Liberec and later graduated from the University of Textile and Mechanics in Liberec (now Liberec Technical University). Already as a child he took an eager interest in gliders and automobiles. After graduation he found a job at the Mladá Boleslav branch of Škoda in 1968; after some time he was transferred to the R&D department. In August 1968 he protested against the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact forces, for which he was later forced to quit his job at Škoda. He worked the next sixteen years as a driver and a coalman at the Mladá Boleslav Coal Depot. He joined the Czechoslovak Socialist Party and made his way up into its central committee. In November 1989 he was one of the founding members of the Civic Forum in Mladá Boleslav, he participated in negotiations regarding the surrender of power and the departure of the Soviet soldiers garrisoned in the city. He also served as the vice chairman of the city committee, as a member of the privatisation committee, as the deputy mayor of Mladá Boleslav, and as a board member of the Mladá Boleslav Transport Company.