„We returned to the bosom of our country, but we remained a Slovak minority - I‘m still sorry, but it‘s true.“

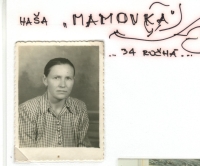

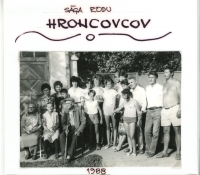

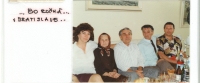

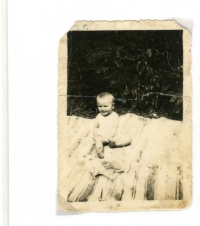

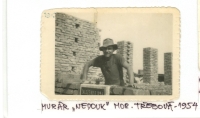

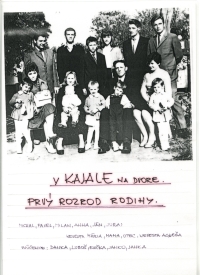

Michal Hronec was born on June 11, 1935 in the then Kingdom of Hungary, in the town Slovenský Komlóš or otherwise called Slovenská Chmelnica. Mother Anna, as single Rafajová, grew up only with her father, as her mother died when she was two years old. The father of Michal Hronec, was four years older than his mother. After his father‘s death, the family remained very poor. He had no choice but to immediately work for the farm he had spent the next ten years with. Michal‘s parents got acquainted as very young, the so-called date organized by local elderly ladies, mostly widows. The wedding took place in 1934 and after Michal, three more siblings joined the family. Life in the Slovak Komlóš was very good, except for the desire of the Hungarian nation to become united. In practice, this meant that Slovaks were not allowed to work, for example, at a municipal office or in other official or administrative positions. There were only two options. Either the person had to be Hungarian or he had to make a Hungarian surname and, of course, speak the Hungarian language. Michal felt it especially in kindergarten or school, where they only learned Hungarian and were not allowed to speak Slovak. His parents, for example, felt it at the municipal office when they wanted to process applications. If they did not speak Hungarian, they could not do it. Without this, life in Hungary would be very good, as the country was fertile and the family never went hungry. After the Second World War, in 1947, Michal‘s family was relocated. They were in a transport that headed to Galanta, then continued to the village Kajal, where they got a house after three weeks. Even though they had returned to their homeland, they still felt like a minority, as many locals did not accept them best. The trip lasted two and a half days. In 1950, Michal left for Bratislava where he became a carpenter‘s apprentice in Montostav. Unsatisfied, he wanted to become a mason‘s apprentice, but was accepted to an industrial high school, so he no longer continued to make a decision. Instead of Bratislava, he had to study in Prostejov, Czech Republic, until 1955. Subsequently, he returned to Bratislava, where he obtained a job in the Czech Republic as an assistant at the Regional Hygiene Epidemiological Station. However, he worked there for only two months because he was called up for compulsory military service. Michal joined Galanta, where they decided to be placed in Litomerice, as sapper. Admission to the national company Pozemné stavby Bratislava followed. At first he worked again as an assistant, but after a year he became the construction manager of two large buildings. In 1960, Michal married a deeply religious woman. It was no secret that Michal and his father were members of the Communist Party. He later became the director of a plant for five years, from which he was fired for allegedly violating intra-party democracy. For the next three years, he became the head of the technical development rationalization department in the corporate directorate. There he received an offer for the director of the construction of the house of trade unions, which he carried out until 1981. After privatization, Michal became a consultant and later, after a change of owner, a production deputy. He worked in the company until 1999, when he was fired. After 2000, Michal became a construction foreman at a friend‘s company, and later also helped young boys learn technology. At the age of 84, he ended his construction career. The memorial even followed the writer‘s career and wrote a saga of the family, which he published under the title „Unwritten Memories - My Father‘s Dream.“ He also collected verses from his birthplace, which he grouped together in the book „Behind the Bigger Sky“. He is currently a member of the Association of Slovaks from Hungary, and also works in the Geological Association of Slovaks from the lower region.