With faith and hope through the hardships of life

Stáhnout obrázek

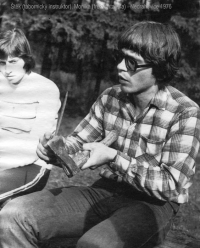

Petr Goldmann was born on May 9, 1955 in Prague as the second son of a family that supported the communist regime. The parents worked in high posts and even studied in Moscow, where their first son was born. Petr Goldmann‘s father was imprisoned for resistance during World War II and went to two concentration camps - Auschwitz and Buchenwald, where there were two secret lines - Christian and Communist. He became involved in the second structure that helped the environment survive. They were led by Josef Frank, whom Petr Goldmann‘s father considered a very honest man, so he was surprised to be tried and convicted in a fabricated trial in the 1950s. Petr Goldmann attended Křesomyslov Elementary School with extended language teaching, but his performance was not good. During the events of August 1968 the whole family was in a cottage in Senohraby; the parents of their older brother were allowed to go to Prague, but the younger thirteen-year-old Petr was not. He listened to Czechoslovak Radio for days and looked forward to the city, where he saw an excited city and felt the atmosphere of defiance. The parents did not agree with the invasion of Soviet troops. This period was important for Petr Goldmann, he refined his views and gradually went his own way. He joined the Scout and reconsidered his view of the world - both the Communist Party and the believing Christians - and converted to Catholicism. After a year at the lumberjack school, where he found out that this would not be his way of life, he got to Karlovy Vary for a pedagogical high school and studied with excellent results. However, he did not receive a recommendation for university. He started working as an educator at a boarding school in Lhotka, Prague. At this time, he already knew his current wife and began studying psychology by distance, because distance learning was not so much guarded by the regime. After graduation, the couple went to Karlovy Vary and worked in Ostrov nad Ohří, his wife Marie was a doctor. They belonged to the so-called gray zone - they were against communism, but at the same time they did not belong to active dissidents. They said several times that they were emigrating, but they were kept here by their aging parents. Petr Goldmann was not allowed to have interns in his ward and was often accused of religiously influencing his patients. His superior was a great communist. In 1991, their older son Jakub went to school and the family moved back to Prague with his younger son Šimon. The Goldmanns began working in a psychiatric hospital in Bohnice, where they worked until recently. Together with the Špinks, they founded the organization Cesta domů, which helps dying patients not to suffer and stay in the care of their families. Petr Goldmann is a recent retiree and faith is very important to him, which gives him the positive security that is important to him. It agrees very much with Václav Havel‘s motto „Hope is not the belief that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something will make sense - no matter how it turns out.“