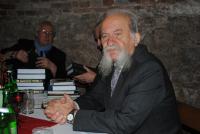

Mykola Mušinka

* 1936 †︎ 2024

-

“Those were the 1950s, when I tried to swot Russian, at school we had only coal days, flu days, so in majority of time we were at home, in the village. We didn´t have the electricity at home back then, and so I used to read by the lamp to ladies, our neighbors who were spinning a wool. They used to tell me: ʻRead us something from those books you have for school.ʼ And so I read them Pushkin – I loved Pushkin, I even knew some passages by heart - they didn´t understand me! Then I read them Shevchenko – poem Katerine. They started to weep! On the next day even more women came to spin. ʻMykolajko, read us in our language!ʼ They understood Ukrainian. And I paused – what a Russian I am when my mom doesn´t understand me, and when I read Shevchenko she cries as it moves her so much! Thus I changed my study subject from Russian to Ukrainian and yet I took the school leaving examination from Ukrainian afterwards.”

-

“If I stayed at the university and wanted to publish even one line abroad, I would need to file an application to the foreign department, they would have to agree, and only this way I would be able to publish something in other country. Otherwise, I would be tried for a violation of working discipline. It was logical. The state paid for scientific work, so you had to hand in that scientific work to the state. And the state was authorized to decide, whether you could publish it abroad, or not. But when I was just a worker and the state paid me for grazing the cattle and for heating, I could have published a monograph in Paris without them trying me for it, since I didn´t violate the working discipline.”

-

“I was extremely careful in Volyn not to be embroiled in something. No one believed me I came there just to take notes about folklore. They all wanted to go back, even on the next day! Because they found themselves to stay in horrible conditions, the empty Czech houses were already taken by settlers from the East, by Party´s officers and Lemka´s from Poland. There was left nothing for our people. In case some house was free, there were no windows, no doors, and they lodged there even five families. They were terribly disappointed. In 1947 there was a great starvation in Ukraine, people were dying. This was the situation our people were exposed to. When I went home for Christmas, I informed Docent Kapišovský, a Chair of the Cultural Association of Ukrainian Workers: ʻFrom 1947 there are our people. Now is the year 1965 and anybody hasn´t approached them yet. They do not receive our press, they have absolutely nothing. Why couldn´t there perform e. g. Ukrainian Theatre from Prešov, or some other company?ʼ I wrote several reports, At my countrymen in Ukraine, it was called, nothing too spicy, not to cause a problem, and these articles had amazing response.”

-

“One could not hear a Ukrainian word in Kiev back then. The Russian language was everywhere, where a man came, just Russian was spoken. I am a provocateur; I said to myself I was not going to speak Russian in Ukraine at all! This way I raised attention in Ukrainian dissidents. In 1965 it was very tight in Czechoslovakia; the censorship was canceled, so I used to tell them about this. There was a samizdat being issued, I smuggled it to Prešov, from where it was passed on to the West. It worked very well until they caught me in 1965.”

-

“I had an absolute prohibition of publishing; nobody was allowed to employ me, neither in education, nor in the editorial offices, anywhere. Only in the R - worker - category (R – stands for robotník in Slovak – ed. note). In my village they just launched an agricultural cooperative (JRD), so I volunteered there for feeding cattle. I milked cows during the whole winter. Then they needed a cattle herdsman, so I asked my father, 'What if I signed up for a herdsman?' I was already a Candidate of Sciences and a Doctor of Philosophy. 'Would you be ashamed of me?' 'Why? Because of having a job? I would be ashamed, if you were a thief,' said my father, and so I went to sign up. I worked there for five years. I lived in a hut where my friends from Prague visited me. I had correspondence from my herdsman´s hut with the whole world! However, the State Security couldn´t monitor me there, and thus the District Party Committee officially forbade me to graze cattle. So I enrolled in a stoker course.”

-

Celé nahrávky

-

Slovanská knihovna Praha, 06.02.2011

(audio)

délka: 01:41:05

Celé nahrávky jsou k dispozici pouze pro přihlášené uživatele.

A scholar Mykola Mušinka – in touch with the whole world from a herdsman´s hut

Mykola Mušinka was born into a peasant family on February 20, 1936, in Kurov, a Carpatho-Rusyn village in the Eastern Slovak district of Bardejov. He finished the elementary school in his native village and he continued studying on high schools in both Bardejov and Prešov. After his successful graduation at the Charles University in Prague, Mušinka worked for a short time as a high school Russian language instructor. From 1960 to 1972, he joined the newly-established research department of the Ukrainian Philosophical Faculty of Šafárik University in Prešov, where he lectured on Ukrainian history and folklore. Within the years 1963 - 1966, he became a graduate student at the Charles University in Prague and at the University of Kiev in the Soviet Union. However, he had to untimely end his studies because the communist regime accused him of being in illegal contact with Ukrainian dissidents and of being a mediator for publishing their works in Czechoslovakia and in western countries. Yet, in 1967 he managed to gain the equivalent of an American doctorate degree (Kandidatnauk) for his thesis on Transcarpathian folklore at the Charles University in Prague. During the so-called normalization era (1971) he was dismissed from the Prešov University with a strict prohibition of publishing activity. He went to his native village and from 1972 until 1976 he worked in the Kužľov agricultural cooperative (JRD) as a beef cattle herdsman. Interestingly, the Disctrict Committee of the Communist Party of Slovakia in Bardejov forbade him to carry out even this work (supposedly because there were unknown people meeting at his herdsman´s hut, and the ŠtB authorities were unable to monitor them.). From 1976 until June 1990 he worked as a stoker of the Municipal Housing Authority in Prešov. Not long after the rehabilitation (1990) he began working again at his original workplace. In1992 the Academy of Sciences of the independent Ukraine awarded him as the first foreign citizen a scientific academic degree: a Doctor of Philological Sciences (DrSc.). He has been retired since 2003, but he is still active as a scientist, pedagogue as well as a socio-cultural worker. In 2005 the Uzhhorod National University awarded him an honorary degree of Doctor Honoris Causa. Lifelong bibliographical work of Mykola Mušinka represents 73 books (including brochures and it edited anthologies), 260 scientific studies, 1319 popular articles and 466 reviews. Together it comprises 2118 items. His dominant area was Ethnography, but he also devoted himself to literature, art, and history.