People who are able to get together while playing music surely must understand each other no matter what nationality they are

Stáhnout obrázek

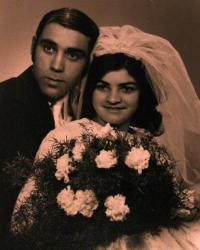

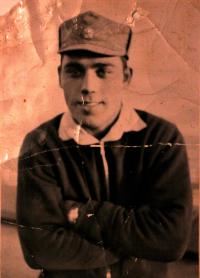

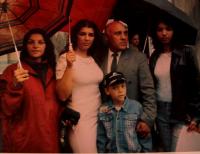

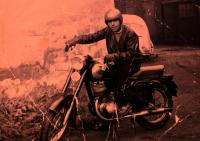

František Gabčo was born March 11, 1948 in Ruská Nová Ves near Prešov into a large and poor Gypsy family to Anna and Štefan Gabčo. In 1962 he began studying at the vocational school for miners in Ostrava, but he did not complete his studies. In 1963 he moved with his father to Rotava and he began working for the state-owned forestry company. During the following two years his whole family moved to Rotava as well and they settled there permanently. In 1967 he directly witnessed the so-called second eviction from Přebuz. During the events of August 1968 he was doing his military service in the anti-aircraft defense unit. In 1973 he married Jiřina and they had four children. Their neighbour Anna Marešová became their family‘s protector as well as the godmother to their children. František quit his work in the forest after his wedding and he began working in the factory Škoda Rotaz where he - with the exception of a short stay in Kladno - worked until his retirement. He refused to get involved in the Velvet Revolution. In 2003 and 2004 he was active in the civic association Amoro Dživipen.