August invasion affected the fate of everyone in Hradec Králové

Stáhnout obrázek

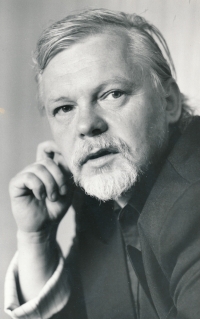

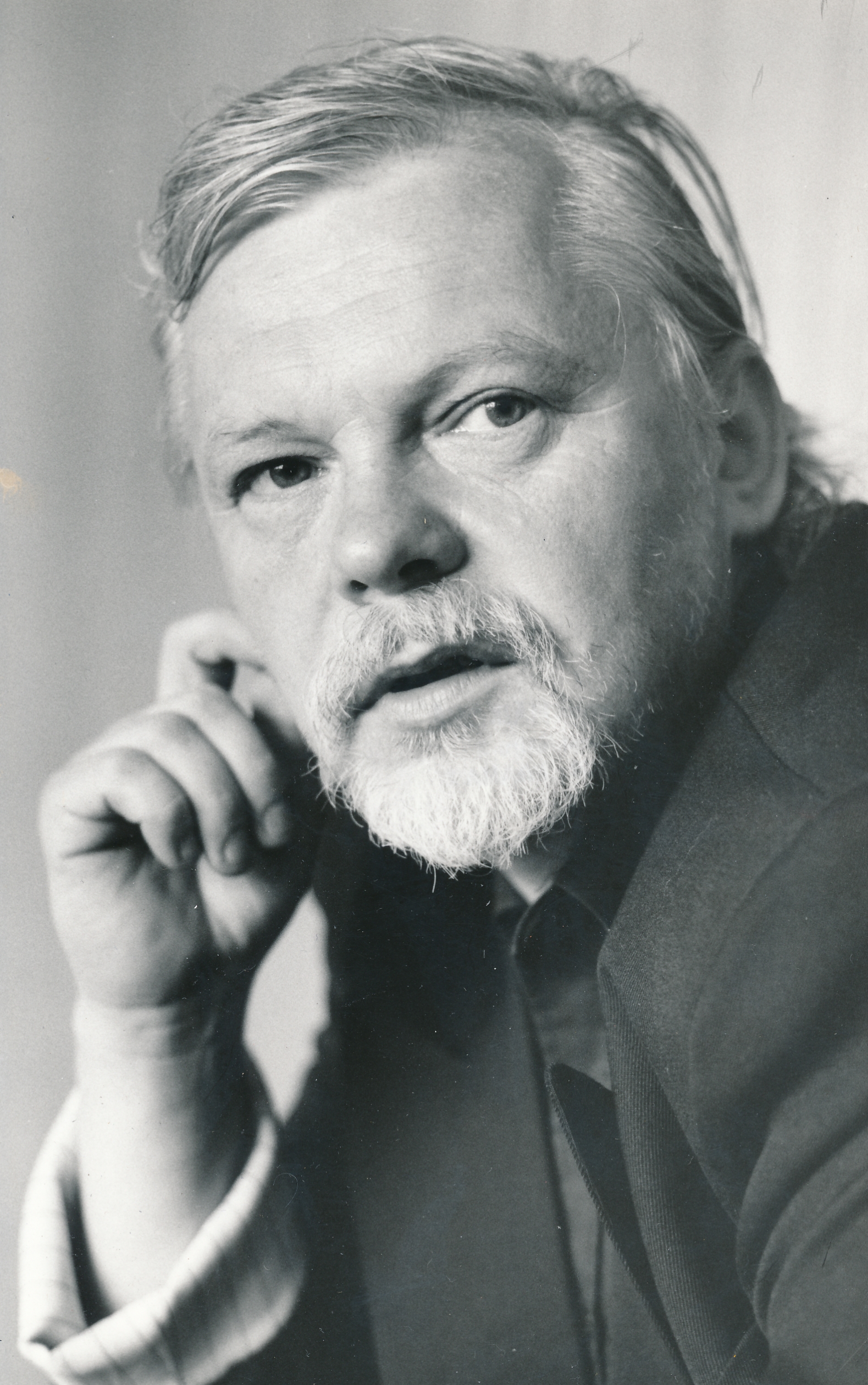

Igor Froněk was born on 18 February 1946 in Svitavy to the Froněks. His mother Tamara Džemelová came from Rostov-on-Don (USSR) and met her future husband Karel Froňek during the war during forced labour in Ulm, Germany. In 1953, the then seven-year-old Igor went to his mother‘s birthplace with his mother and younger sister. At the border, Soviet soldiers arrested them and took them to a prison in Mukachevo. After several months of investigating the reasons for their return, they were released to their grandmother in Rostov-on-Don. My father came to visit the family after a year, but by then my mother was already arranging the documents for her return to Czechoslovakia. They returned to Svitavy in 1955 and after a year, their Rostov grandmother came to visit them permanently. They moved to Jeseník, where Igor Froněk finished primary school. He continued his studies at the film school in Čimelice and after graduating in 1967 he joined the Czechoslovak Radio in Hradec Králové as a technician. He was working there on the twenty-first of August 1968, when Warsaw Pact troops entered Czechoslovakia. And he was among the employees who actively participated in the improvised broadcasts of Czechoslovak Radio from Hradec Králové. After the onset of normalisation, he passed the checking process, but was dismissed in 1978 anyway. For half a year he could not find a job until he ended up in the letter sorting room at the post office. After a year he got a job as a sound director at Jiří Srnec‘s Black Theatre. In 1982 he started working as a sound director in the vocal ensemble Linha Singers. From 1979 State Security focused on him, like most of his radio colleagues from August 1968. State Security kept a file on him as a person under investigation from November 1979, after six months they transferred him to a signal file under the code name Ivo (KR-984675 MV) and from 1983 they kept Igor Froňek as an agent under the code name Vopršal. Igor Froněk did not learn this fact until the 1990s. Because he did not knowingly sign the cooperation with State Security, he considered clearing his name in court. After the Velvet Revolution, Igor Froněk returned to work for the radio. In 1997, he was the director of the first private East Bohemian television. In 2024 he was living in Příbram.