Where our native villages stood, the military area Ralsko was later established

Stáhnout obrázek

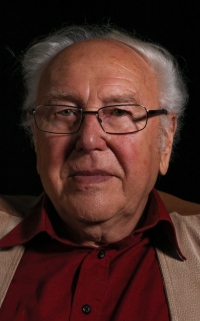

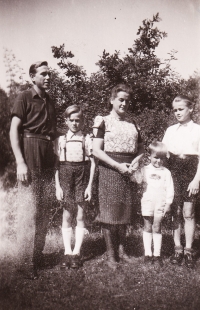

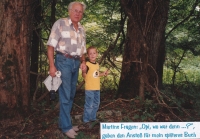

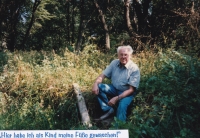

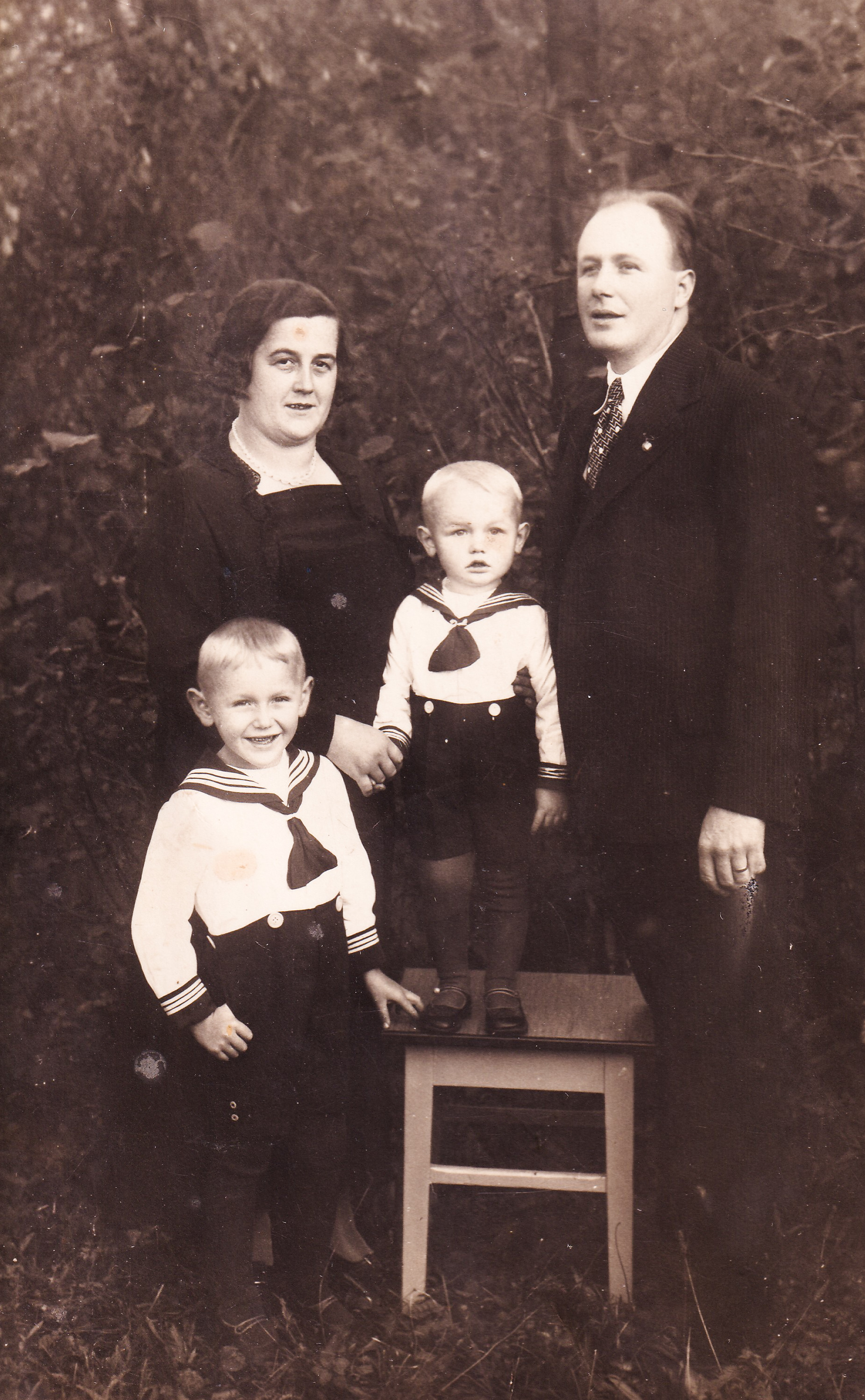

Werner Friedrich was born on 16 November 1931, the eldest son of Heinrich, a shoemaker, and Elsa, a seamstress, in the village of Palohlavy (Halbehaupt) near Mimoň. The village belonged to the so-called Upper Villages (Oberdörfer), where the German-speaking population was predominant, although most people could also speak Czech. During the 1930s, his father Heinrich Friedrich changed his occupation and became a dealer in agricultural and other machinery. After 1938 he even became mayor of the village, and got along well with the Czech and mixed families, of which there were many in the village. Although his father joined the SS, he later regretted it and was recruited into the German army, although as mayor he did not have to. Gradually, more sons were added to the family, the youngest was born on April 1, 1945, and his father never saw him again. The deportation of the German inhabitants was fierce in Palohlavy, it took place in the summer of 1945. The first wave came on June 11 and the second wave on June 25, which already included the Friedrich family, i.e. the mother, almost fourteen-year-old Werner, almost eleven-year-old Erich, seven-year-old Heinz and two-and-a-half-month-old infant Dieter. They took with them only what they could carry, the transport from the station in Mimoň to the German border was in open coal wagons. Soldiers of the Czechoslovak army drove them across the border on foot, leaving them to their fate across the border. For about four weeks, the mother and children made their way through the surrounding villages, then through Dresden to the Graupa refugee camp and from there finally to the village of Unterpaissen. After two years, a friend of the father took them to Plauen, where they settled for good. The family never received any news of what happened to their father. Werner Friedrich first apprenticed himself as a baker to provide the family with at least some money and bread. Later he became a teacher, studying history and German by distance learning. After German reunification, he became a school board member in Saxony. The expulsion ended his childhood, but he was still drawn to where he was born. He soon learned that Palohlavy and most of the other Horní Vsi had become part of the Ralsko military area, but after 1993 he often came here with his children and grandchildren. He also founded a compatriot association and cooperated with his Czech friends, going every year to the Náhlo festivities.