She secretly transcribed 60 banned books

Stáhnout obrázek

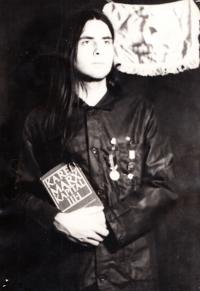

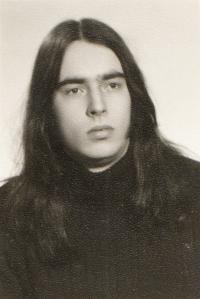

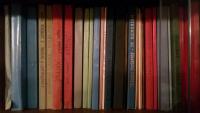

Tatjana Dohnalová, née Hejnyšová, was born on 4th November 1950 in Děčín, where she was being raised by her grandmother until she was five years old. Her parents Vladimír and Ludmila Hejnyš, who were actively involved in the Communist Party, meanwhile studied the University of Economics in Prague. Táňa began living with them in Prague in 1955. Two more children were later born into the family - Táňa‘s brother Evžen who was six years younger, and eleven years younger Oleg. Tatjana Dohnalová belongs to a generation that began forming their opinions in the second half of the 1960s, and her views often differed from those of her parents who were Party members. Both her parents were expelled from the Communist Party in 1969. Táňa graduated from the general secondary school with extended language instruction around that time. She then married Jindřich Dohnal and she started a family. She began working in the cooperative Pokrok (‘Progress‘), where she got acquainted with Pavel Rychetský. In 1977 she and her husband signed Charter 77, but following Pavel Rychetský‘s advice, she later withdrew her signature. Mr. and Mrs. Dohnal had a little daughter at that time, who would have been left without parents if they had been both imprisoned. Their son was born in 1978. In 1978 Táňa began collaborating with Jiří Gruntorád and she started transcribing blacklisted books for his samizdat series Popelnice (‘Dustbin‘). She later started copying so-called Infoch documents as well, which provided information to those who were interested in the activities of Charter 77. During eleven years she transcribed 60 samizdat books and for the entire time she managed to keep her activity completely unnoticed by the authorities. Both her brothers emigrated in the 1980s.