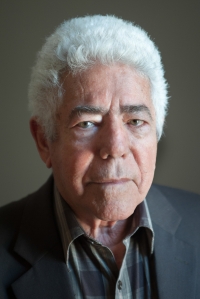

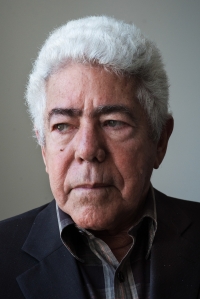

No, I do not have to thank the Revolution, but I have to thank God

Stáhnout obrázek

Ángel de Fana Serrano was born in 1939 in Havana. Being a good student, he got a scholarship at the Havana Business Academy, where he focused on Accounting and English. Until the confiscation of 1961, he worked in a footwear factory. Very soon after the triumph of the Revolution of Fidel Castro, he realized the Communist character of this project and joined the Martian Democratic Movement in 1960. Two years later he came to the head of the movement, whose objectives were to weaken the regime with sabotage, disarmament of militias and anti-Castro propaganda. Ángel de Fana Serrano was arrested in 1962. He was accused of the intellectual authorship of an attack in which a pro-government soldier was killed and of the organization of an uprising that took place in August 1962. He was transported to a place known as Las Cabañitas or Point X, the exact location of which is unknown. There he was subjected to interrogations in very bad conditions for about 37 days. Later he was transferred to La Cabaña, and in 1963 he was sentenced to 20 years in prison. He became one of the best-known „planted“ prisoners, that is, prisoners who declined any cooperation with the regime, passing through several prisons, including the Combinado del Este, Bonyato, Guanajay and La Cabaña. He opposed the negotiations carried out by the Cuban government with the United States on his possible release, arguing that his freedom could not be conditioned. He was finally released in 1983 and went into exile in the United States. He worked to denounce the crimes of the Cuban regime on La Voz de CID [CID‘s Voice] radio until the early 1990s and was one of the leaders of The Planted for Freedom and Democracy in Cuba, which supported opponents and political prisoners in Cuba.