The war and communism divided our family forever

Stáhnout obrázek

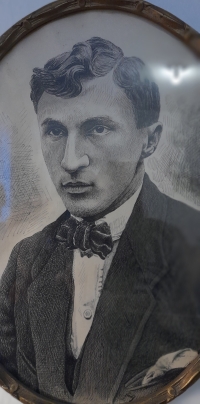

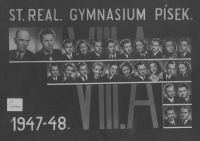

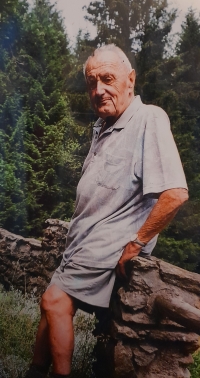

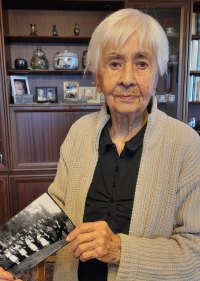

Růžena Černíková, née Chramostová, was born on 16 February 1929 in Milevsko. Her father, Ladislav Chramosta, worked for the then tax administration, while her mother, Anna Vaňková, was a housewife. The family moved around because of her father‘s job, until in 1939 they settled in Písek, where her mother‘s family came from. Grandparents Eduard and Josef Vaňkovi ran a cinema in Písek, which they had to sell after 1918. During the war, their uncle Jiří Beneš was arrested for listening to illegal broadcasts. He died in Pankrác prison. Uncle Eduard Vaněk was killed by a sniper during the Prague Uprising. Aunt Věra Vaňková with her husband Ing. Viktor Ferda, who was Jewish, prudently fled Czechoslovakia and worked for the government-in-exile in London. They emigrated again in 1949. Růžena Černíková graduated from the grammar school in Písek in 1948. The communist regime hit her former classmates hard, who were arrested by State Security and sentenced to long sentences. In August 1948, she married Helmut Pankratz, an undeported Austrian, and moved to the village of Lenora, near the Austrian border. Her husband emigrated to Austria around 1953 because of discrimination, while Růžena Černíková remained in Lenora with her one-year-old daughter. She then lost her housing and returned to her parents in Písek. She and her husband maintained friendly contact, but they did not live together again. They formally divorced after ten years. From the 1950s she worked as a worker in the South Bohemian Fruta factory, later in the office. In 1957, her supervisor Antonín Liška emigrated with his family to the West in a tanker of a freight train, which also affected her, and as a warning she was reassigned with other colleagues to heavy manual labour. In 1960, she married for the second time to Jaromír Černík. They were in Austria at the time of the August 1968 occupation and considered emigrating, but eventually returned. From 1983 she worked as a court translator of English and German, worked at the Research Institute of Aeronautical Engineering and specialized in legal translations. After 1989, she met her aunt Věra Ferdová, who came to visit after forty years. She worked as a translator until she was 95, in August 2025. In 2025 she lived in Písek.