Vždy jsme věděli, že jsme Bulhaři

Stáhnout obrázek

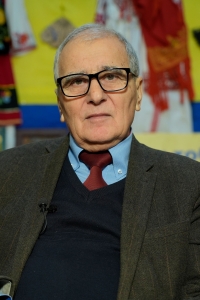

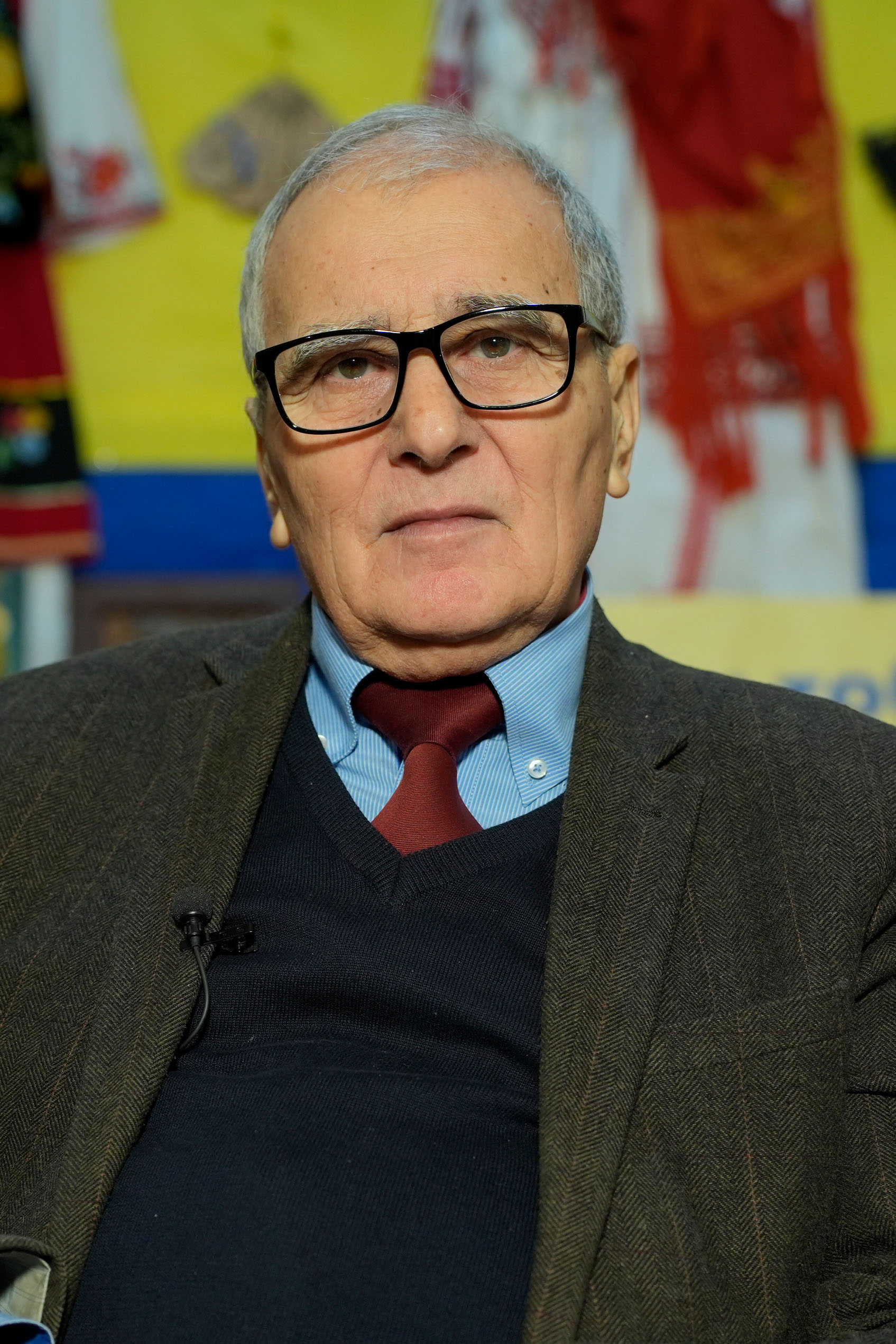

Dmytro Terzi je etnický Bulhar, ředitel Všerukrajinského centra bulharské kultury v Oděse. Narodil se 16. února 1944 ve vesnici Vynohradivka (do roku 1948 Burgudži) v Oděské oblasti v době rumunské okupace Besarábie. Ve vesnici kompaktně žila početná bulharská komunita, takže jeho prvním jazykem byla bulharština. Rusky se naučil, až když chodil do sovětské školy. Po absolvování školy snil o herecké kariéře, ale všechny tři pokusy o nastup na divadelní vysokou školu ztroskotaly na jeho bulharském původu. V letech 1963-1966 sloužil v raketovém vojsku sovětské armády u Pskova (RSFSR). Po návratu z armády studoval dálkově na oddělení Fakulty romanistiky a germanistiky Oděské národní univerzity I. I. Mečnikova a současně navštěvoval školu Intourist pro průvodce a překladatele v Moskvě. V roce 1970 se kvůli tlaku okolí a požadavkům pro práci se zahraničními turisty stal členem komunistické strany. Pracoval v oděské pobočce sdružení Intourist, organizoval návštěvy zahraničních turistů a doprovázel sovětské skupiny v zahraničí. Po roce 1991 se pan Terzi stal jedním ze zakladatelů bulharské komunity v Oděse. Od roku 1999 vede Všeukrajinské centrum bulharské kultury.