„Don’t take what doesn’t belong to you. What belongs to you should not be given to anybody.“

Stáhnout obrázek

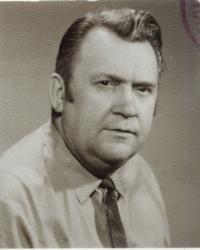

Colonel in retirement Jaroslav Vrtálek was born in the Olomouc region and he learned the saddle-maker‘s trade. After the occupation of Czechoslovakia he was sent into forced labour to Germany to Königsberg (Královec, present-day Kaliningrad) in the former eastern Prussia. In summer 1939 during the journey through Poland, he jumped off the train and he joined the Czechoslovak units which were being formed in Bronovice. After the occupation of Poland he got with the others to the Soviet Union. Via Kamenec Podolski, Olchovka, Jarmolinec, Suzdal and Odessa he eventually arrived to Palestine in 1941. Jaroslav Vrtálek fought at Tobruk, serving with the antiaircraft machine-guns Bofors. When the fighting was over, he was transported on the Mauretania vessel via South Africa to Britain. In Britain he trained for a tank brigade where he served as a dispatch rider. He suffered a serious leg injury at Dunkerque, and he returned to Czechoslovakia only in October 1945. After the war he was receiving a partial disability pension, but he continued serving in the Czechoslovak army in a tank unit. He retired holding the rank of lieutenant colonel and he lives in Prague-Bohnice.