We were very interested in making something happen under democratically established rules

Stáhnout obrázek

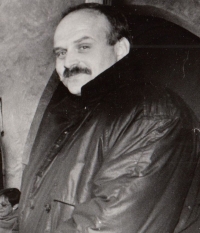

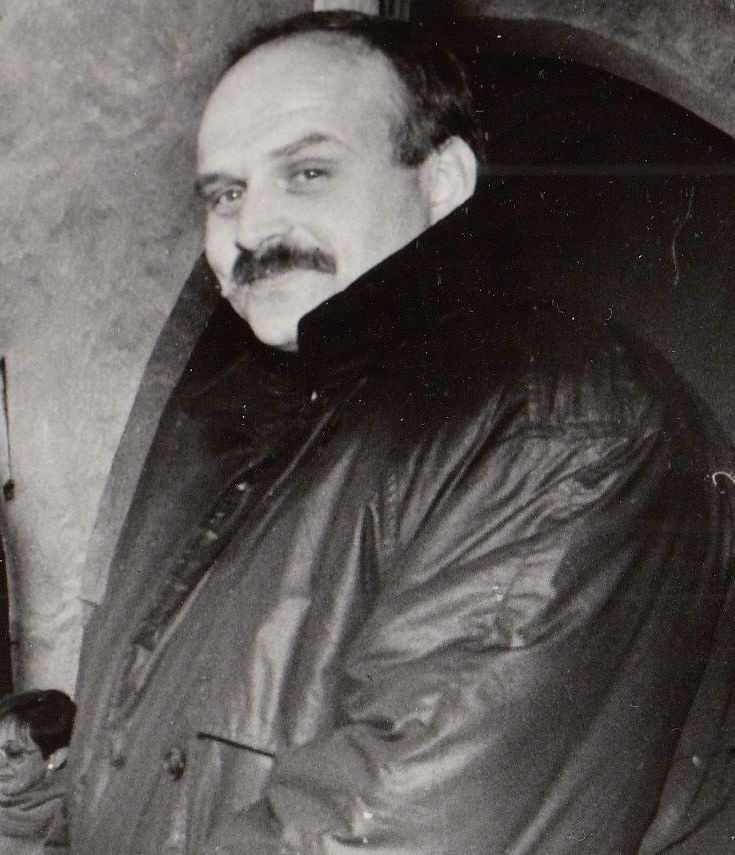

Jan Vondrouš was born on 26 September 1953 in Pilsen to Marie and Bořivoj Vondrouš. His parents had never been members of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ), and from an early age, they led their son to a similar mindset. His dissatisfaction and disagreement with the communist regime culminated in 1989 when he signed a petition called Several Sentences, which he then actively spread in southern Bohemia. He was a direct participant in the November 1989 demonstration in Prague. On 19 November 1989, he was at the birth of the Civic Forum (OF) and actively participated in the Velvet Revolution in Český Krumlov. He participated in transferring power from the communist leaders in the Český Krumlov region to the OF. He ran as a candidate for the Civic Forum in the first free municipal elections. In 1990, he became the first post-war mayor of Český Krumlov to emerge from democratic elections, serving over two terms until 1998. He was one of the main initiators and creators of the post-Soviet transformation of Český Krumlov into a centre of cultural tourism. In 1991, he joined the Civic Democratic Alliance (ODA) and later the KDU-ČSL. After leaving politics, he opened a puppet museum and wine shop called Krumlov Inspirations, which he still runs today (2023). In 2023, he lived with his wife, Hana Vondroušová, near Český Krumlov in Slupenec.