Father was arrested by the NKVD in Ukraine and mother was told that he died of pneumonia. Only years later did we learn the truth

Stáhnout obrázek

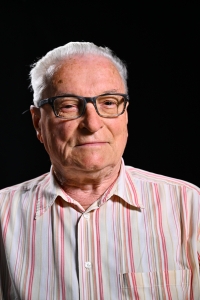

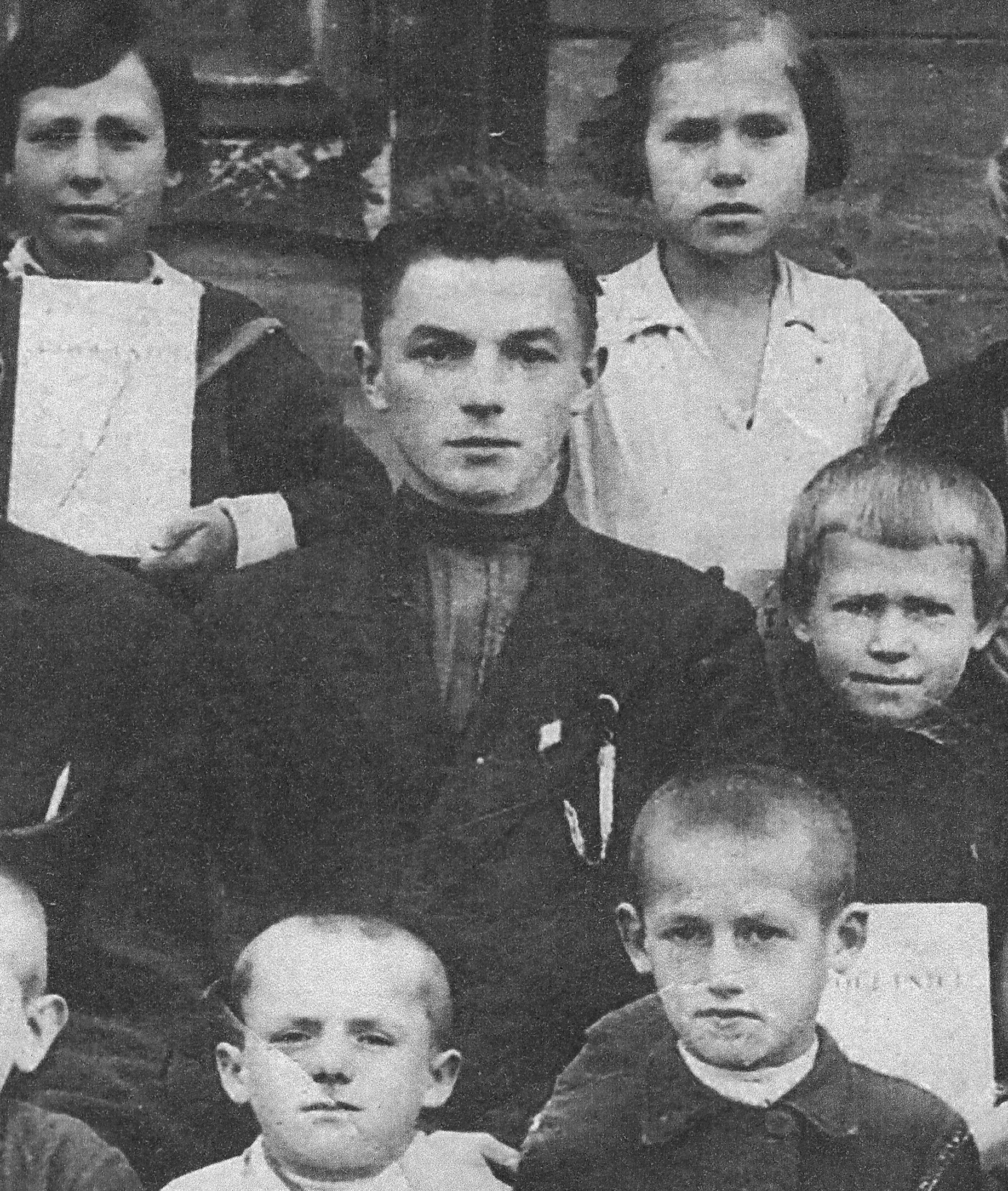

Boris Višněvský was born on 19 March 1937 in the village of Malinovka in Zhytomyr region, Ukraine. Originally a German village, Malindorf was historically settled by Czech colonists, and at the time of Boris Višněvský‘s birth it was a predominantly Czech village with a Ukrainian minority. His grandfather Antonin Fedorovich Chudoba came from another Czech village, Malá Zubovščina. His father Jaroslav Chudoba-Višněvský was a teacher and school director in Malinovka. In November 1937, just a few months after the birth of his son Boris, he was arrested by the NKVD and illegally executed, shot. His wife, Anna Višněvská, was falsely informed that he had died of pneumonia in custody. Anna Višněvská never married again. It was not until the late 1980s that the Soviet authorities posthumously rehabilitated him. The family lost everything during World War II. The front passed through the village, they experienced fierce fighting. The Višněvský family house was hit by shelling and burnt down, the family suffered from hunger. Boris Višněvský saw with his own eyes how the German soldiers burned a man who was hiding with his family in a dugout and wanted to prevent the German armoured vehicles from crossing it. They burned him nailed to the barn where the family had the rest of their possessions. He also saw the execution of his aunt, who was publicly hanged on a gallows by the Germans. The family was helped by their Czech neighbours and the village had very tight realtionships. After the war, during the period of the re-emigration of the Volhynian Czechs to Czechoslovakia, the Czechs from Malinovka were unlucky; the 1946 intergovernmental agreement on the re-emigration of Czech compatriots did not apply to Malinovka, as it lay outside the historical borders of the then Volhynia province. Despite this, the Višněvský family managed to be included in the re-migration programme and went by cattle carriage to Český Jiřetín. They got housing in the house of the expelled Sudeten Germans. Here Boris Višněvský went to primary school with other children from the ranks of the re-migrants, and later they moved to Chomutov. After finishing primary school, he graduated from the secondary technical school in Teplice, majoring in glass machinery. After school he got a placement in the Moravia glassworks in Kyjov. In 1960 he met Drahomíra Průšová, whom he married in 1961 and a year later they had their first son. They were unable to find housing in Kyjov and moved to Teplice, where he started working as a revision engineer. There he also worked as a volleyball coach and joined the Communist Party. His second son was born in 1964 in Teplice. However, they had to move from there because of the first son‘s asthma, so he accepted an offer to work in the prison in Všehrdy. He provided work for the convicts, later worked in the personnel department, for a short time he was a political worker, then deputy head of the department. He stayed in this position until 1990, when he was fired during the checking process because of his membership in the Czechoslovak-Soviet Friendship Union. He worked for a short time at the mine. He then received a full pension, but went to work as a mechanic for the army at the radio engineering brigade, where he remained until 1999. Then he was a guard at the secondary technical school of energy in Chomutov. He retired in 2012. In 2023 he was still living in Chomutov.