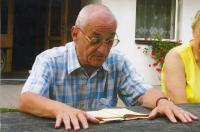

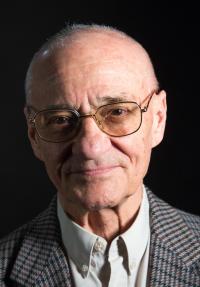

From atheist to parson

Jaroslav Vetter was born on 18 November 1935 in Prague. After graduating from the Komenský Evangelical Faculty of Theology, he served as vicar of the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren in the congregations in Děčín (1959) and then Chomutov (1962-1967). In the late 1960s, early 70s he helped build up a camp in Chotěboř and maintain it as church property. In the first years of normalisation he also functioned as secretary for the children apostolate of the Synodal Council of the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren. As the political situation worsened, he resigned from the post and became parson of the Střešovice congregation, where he remained until the year 2000. Over the years he wrote many articles for children in Czech Protestant periodicals, mainly in the monthly magazine Český bratr (Czech Brother), which he also edited.