A bomb that whistles is a bomb that is falling on your head

Stáhnout obrázek

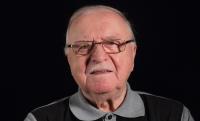

Miroslav Toms was born on 5 July 1931 in Benátky nad Jizerou. He had moved around with his parents several times. They settled in Prague where he stayed up until his emigration. During WW II. he witnessed historical events, survived the February 1945 shelling of Prague as well as the retreating German soldiers at the end of the war. He had lived with his parents in Podolí for a long time, studying at a grammar school in Truhlářská street. His unfavourable cadre profile nearly prevented him from graduating in 1950, and also complicated his application to university. After graduating from the Czech Technical University, he worked in the Tesla company for several years and later in an engineering company. In the 1960s, he became of interest to the secret police. First, he was interrogated in Bartolomějská street and later, a secret agent was meeting him in the Družba hotel. Following the 1968 invasion, he decided to leave the country for Germany, where he had spent the next twenty-seven years of his life. After his return to the Czech Republic, he filed a lawsuit to have his name removed from the list of secret police informers and from an internet archive, and he succeeded. He has a son and a daughter and is married for the third time.