They needed to install an atmosphere of fear

Stáhnout obrázek

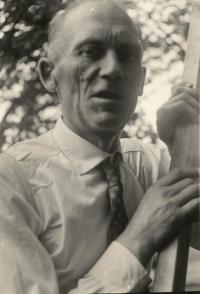

Prokop Šmirous was born August 29, 1939 in the village Leština u Světlé, where his parents owned a farm with 31 hectares of arable land and four hectares of pastures and meadows. Just like the other large farmers, Prokop‘s father refused to join the Unified Agricultural Cooperative during the first wave of the collectivization process. In June 1950 he was therefore arrested by the StB and on May 19, 1951 he was sentenced in a show trial ‘Kritzner and Co.‘ to twelve years of imprisonment. The authorities subsequently confiscated the family‘s property and several months later they made Prokop‘s mother and her three children get on a truck and they transported them to another region. Prokop‘s father returned from prison only ten years later with damaged health. Prokop was thus forced to spend his adolescent years and the most complicated period of his life without his father. Prokop did not give in and in spite of his negative political and class profile and after many difficulties he managed to graduate from the University of Agriculture in Brno and in 1983 he was awarded the CSc. (candidate of sciences) degree.