I was painting, and suddenly it was a mess. The window blew out in my head. War wound...

Stáhnout obrázek

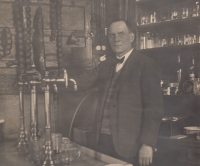

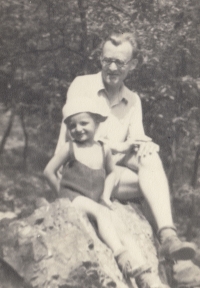

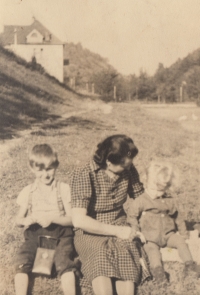

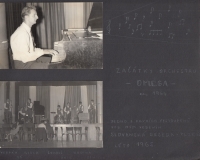

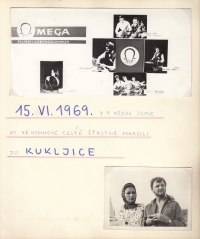

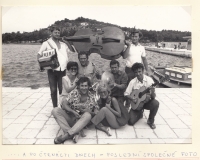

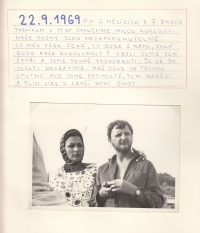

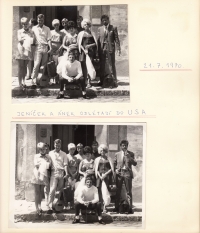

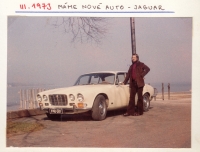

Lubomír Schimmer was born on 26 September 1939 in Prague to Růžena Schimmerová, née Vedralová, and Jan Schimmer. His father was a teacher, his mother worked in a clothing store. He spent his childhood in Podmoráni in Úholicky. In 1944, planes flew over their house. In his grandfather‘s pub a missile broke the window and the shards cut Lubomir‘s head. In Velké Přílepy he experienced the arrival of the Red Army, one sergeant stayed at their home. Together with his brother, he trained at the XIth All-Sokol Meeting. In 1956, he trained as a waiter at the Continental Hotel and began working at the Vienna Café. In 1961 he married Anna Kratochvílová, and their son Miroslav was born. After his marriage, he worked at the Old Iron Works in Pilsen, then at the Institute of Geodesy and at the Phoenix Café. From 1962 he studied at the People‘s Conservatory in the racing club ET Doudlevka. He founded the band Omega. In 1954 and 1957 they came second in the national competition Looking for new talents. In 1969 he emigrated to Yugoslavia with his girlfriend Veronika Bajgerova and the band Omega, then lived in Austria and Germany. He returned to Czechoslovakia in January 1990. He then married his third wife, Jana Majerová. At the time of filming (2023) he was living as a widower in Horní Plana.