They asked me whether I was a communist and I told them I wasn‘t and that I had no intention to become one

Stáhnout obrázek

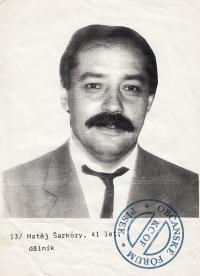

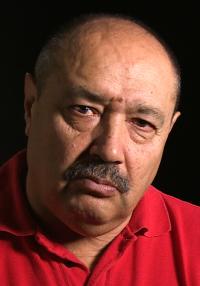

Matěj Šarközi was born on 2 December 1948 in a Roma settlement near the village of Čaradice in mid-western Slovakia as the eighth of nine children. His father was a renowned musician while his mother took care of the household and worked for local farmers. His parents and older siblings faced persecution during WW II from the hands of the Hlinka Guard. After the suppression of the Slovak National Uprising they had to hide in forests to avoid reprisals by the German army which was legitimately suspecting them of supporting the partisans. Despite his parents being illiterate, only speaking Romani at home, and walking several kilometers to school, Matěj Šarközi finished both elementary and a higher agricultural school. He then worked at the Single Agricultural Cooperative in Čaradice after which he undertook compulsory military service in Písek, Bohemia. There he had met his future wife and decided to stay. Up until 1989 he worked in blue-collar jobs. He also chaired a Roma children choir and at the turn of 1960s and 1970s was head of the inspecting committee of the local branch of the Union of Gypsies-Roma. Multiple times he declined an offer to join the Communist Party. After 1989 he worked as an Roma advisor and as field social worker in People in Need. He took part in the first congress of the Roma Civic Initiative in Prague and as a Civic Forum representative was co-opted to the municipal assembly of Písek. From 1997 till 2004 he was a member of the governmental body dealing with Roma issues. There, he advocated for an amendment of the Citizenship Act as well as for compensation of Roma victims of WW II.