My ancestors faced persecution both because of their nationality and their anti-communist views

Stáhnout obrázek

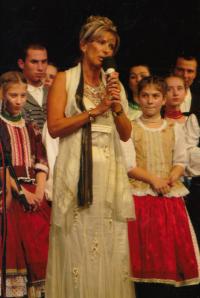

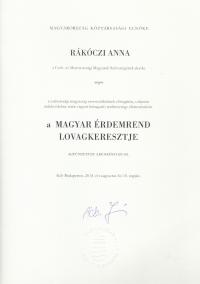

Anna Rákóczi, née Šubová, was born on 1 August 1957 in Nitra into a Hungarian family as the third daughter. She grew up in the village of Čechynce where her father‘s family owned a farm. Her mother‘s family farmed in the neighboring village of Velký Cetín. After the communist takeover, both families refused to hand over their property to an agricultural collective. In the end, it was taken from them by force. Both Anna‘s grandfathers were sentenced to several years in prison. In 1953, her grandma and her mother were forced to move to Žitný ostrov to live in a shop storeroom. Her mother‘s father was imprisoned in Leopoldov and Mírov and worked at a brown coal mine in Handlová. He was released on amnesty in 1956 but even after that he and his wife were prohibited from entering the Nitra region. Not even their children were allowed to pay a visit. Anna therefore only saw her grandparents when she was five years old. Her father worked his whole life in blue-collar jobs and despite not going public, he held strong anti-communist views. In 1968, the family had met Hungarian soldiers who arrived with the Warsaw Pact armies. In spite of her family background, Anna was able to study at a Hungarian economic high school, graduating in 1977. In 1980, she married and moved with him to Ostrava. She worked as an accountant and after the Velvet Revolution in financial consultancy. Ever since 1998, she has been engaged with the Hungarian minority living in Czechia. In 2008, she got married for the second time to František Rákóczi, also an ethnic Hungarian.