I realized that I had no future here

Stáhnout obrázek

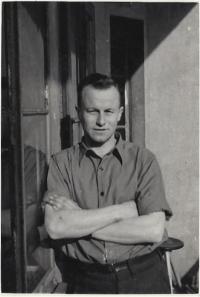

Tomáš Oráč is a Canadian citizen of Jewish origin who comes from Spiš in Slovakia and who lived in Czechoslovakia after WWII. His parents spoke mostly Hungarian or German at home, but he grew up in a purely Slovak village called Granč-Petrovce on the foothills of Mt. Branisko. He learnt Hungarian and German later from his parents and in school, but his native language was Slovak. He and his mother, who worked as a manager of a large farmstead, were excluded from the deportations of Jews. They were hiding his adult sister throughout the war. In 1943 they tried to escape to Hungary, but the attempt failed. They spent the Slovak National Uprising hiding with strangers in the mountains. Tomáš studied chemistry after the war and he began working in a chemical factory in Litvínov. His mother and sister emigrated to Israel and later to Canada. In 1964 he went to Canada to visit his mother and while there he made a definite resolve that he would emigrate there with his entire family. In 1967, after long „struggle“ with Czechoslovak authorities he managed to emigrate legally to Canada with all his family (wife and two daughters). He found employment there as a chemical engineer. Since 1975 he has been living in the United States. He currently resides in Ohio.