In the Auxiliary Technical Battalions they wanted to re-educate us from reactionaries to politically conscious communists

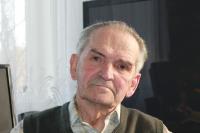

Karel Nováček was born July 3, 1929 in Luka nad Jihlavou. He became a Boy Scout after the Second World War and he was active as a Boy Scout leader in his village until the ban on the Scouting movement. After graduation from the trade academy in Jihlava he served in the Auxiliary Technical Battalions (PTP) in 1950-1953. He was released from the service after signing an agreement that he would subsequently work in the construction industry for the following three years. Karel took part in construction of ammunition depots in Dobronín and of several factory buildings in Jihlava. When the three-year period was over, he began working in the company Meliorace Jihlava and ten years later he found a job in the company Zelenina Jihlava. Karel was actively involved in the second (1968) as well as the third (1989) restoration of the Junák (Czech Boy scout organization).