A lucky star probably brought me to Europe

Stáhnout obrázek

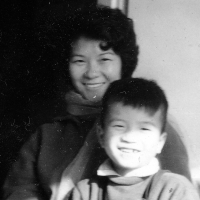

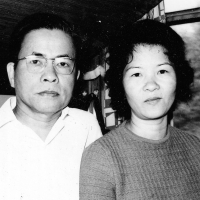

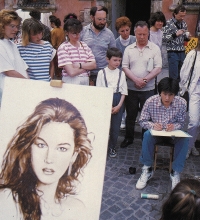

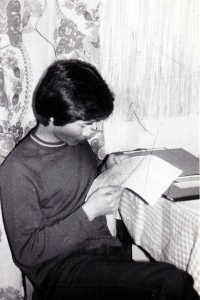

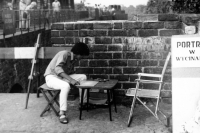

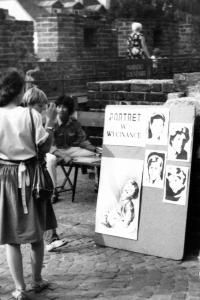

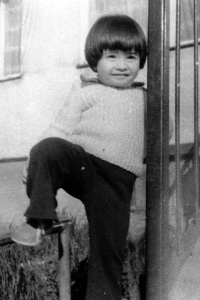

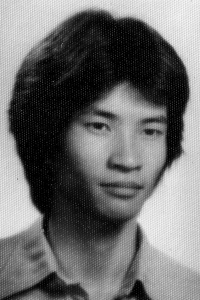

Anh Tuan Nguyen was born on 4 July 1957 in Hanoi in North Vietnam. In 1962, he and his parents left for Polish Warsaw where his father got a job in diplomatic service. The witness attended there a Soviet School for foreigners. He then studied electrical engineering at Warsaw University of Technology. He faced problems and pressure to return to Vietnam because of his relationship with a European woman, Slovak girl Mária, which was according to the Vietnam embassy, unwanted. He was expelled from school. He made money by painting icons and portraying tourists in streets. He moved to Czechoslovakia with his wife and daughter around 1980. The family lived in the East Slovak town of Snina and then in Bratislava. He finished the studies of electrical engineering as an extramural student and he worked as an IT technician in a car factory. After 1989, he started to make his living by painting portraits on Charles Bridge. He moved to Prague.