I couldn‘t have done it any other way

Stáhnout obrázek

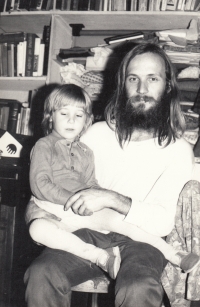

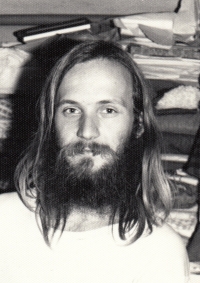

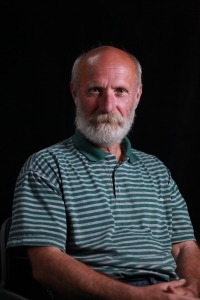

Miroslav Němejc was born on 3 August 1962 in Strakonice. He grew up with his brother Antonín, who was five years older and became his role model. After finishing primary school, he trained as a carpenter in České Budějovice and went to secondary school in Volyně. His brother Antonín signed the Charter 77 in 1978, and thanks to him Miroslav also joined the dissent. He followed Free Europe, read and reproduced samizdat, attended housing seminars and concerts of underground groups. In 1981, the State Security came to Miroslav‘s school, he was searched and interrogated for more than fifty hours. This was followed by expulsion from the secondary school. His brother Antonín was forced by the Secret Police to emigrate, while Miroslav could not find a job in Strakonice. He moved to Prague and worked in military construction. He married and had a son. From 1983 to 1984 he completed his compulsory military service in the labour unit and participated in the construction of the Dukovany nuclear power plant. After returning from the army, he divorced, took custody of his son and returned to Strakonice. He worked as a warehouseman in the Fezko factory. He again became involved in dissent, reproduced samizdat and supported petitions for the release of political prisoners. He became one of the movers of the Velvet Revolution in Strakonice. He has not met his brother Antonín since his emigration. Miroslav Němejc lived in Strakonice in 2021.