The coach´s work showered with medals, while he was snooped on by the criminal police and by counter-intelligence and faced up prison

Stáhnout obrázek

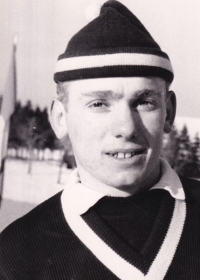

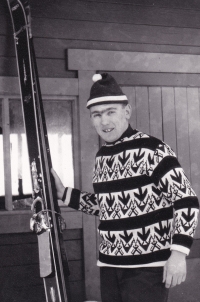

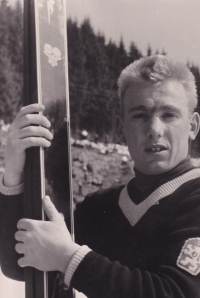

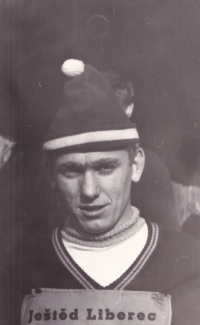

Dalibor Motejlek, a former Czechoslovak ski jumping national team member and a coach, was born on April 17, 1942, in Vysoké nad Jizerou. Growing up in Harrachov meant skiing had become a natural movement to him since his early years. Even as a little boy, he already excelled in ski jumping on the snow bridges, joining the broader selection of the youth national team at the age of fourteen. Despite being trained as a steelworker, he joined the team named Dukla Liberec right after finishing his apprenticeship. He had represented Czechoslovakia in ski jumping several times during the Four Hills Tournament, and at the Winter Olympics in Innsbruck (1964) and Grenoble (1968). He holds the world record in ski jumping (142m) that he achieved in Oberstdorf, Germany, in 1964. His racing career ended with a severe injury that happened during his training in the Tatras, in 1969. He worked for Dukla Liberec as a coach and he became the most successful coach of the Czechoslovak national team in ski jumping in the 1980s. His charges won one gold, two silver and four bronze medals at the Olympics and World Championships. After the Olympics in Sarajevo in 1984, he was followed by the Military Counterintelligence, which created a file on him. He was also investigated by the criminal police for allegedly trafficking in sports equipment. He was not allowed to travel to democratic Western Europe for almost a year and was fired from the position of the head coach of the national team. His accusations proved unfounded and he returned to the Czechoslovak national team. After the returns from a capitalist foreign country, he had to report to the Military Counterintelligence, which kept him as a confidant. He claims he didn‘t know about it. There is no evidence in his file with the code name Rogalo that he actively cooperated with the Military Counterintelligence and reported on people around him. In 1988, he became the coach of the national team of jumpers in the USA, where he remained until 1992. In order to work in the USA, he arranged the termination of membership in the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. He was also one of the pioneers of ski jumping in South Korea. He then worked as a youth coach for Jiskra Harrachov. In 2022 he lived with his wife alternately in Karlštejn in his son‘s family house and in Harrachov.