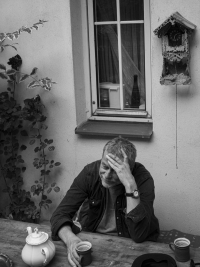

The 80s, it was a peaceful work and cheerful interests

Stáhnout obrázek

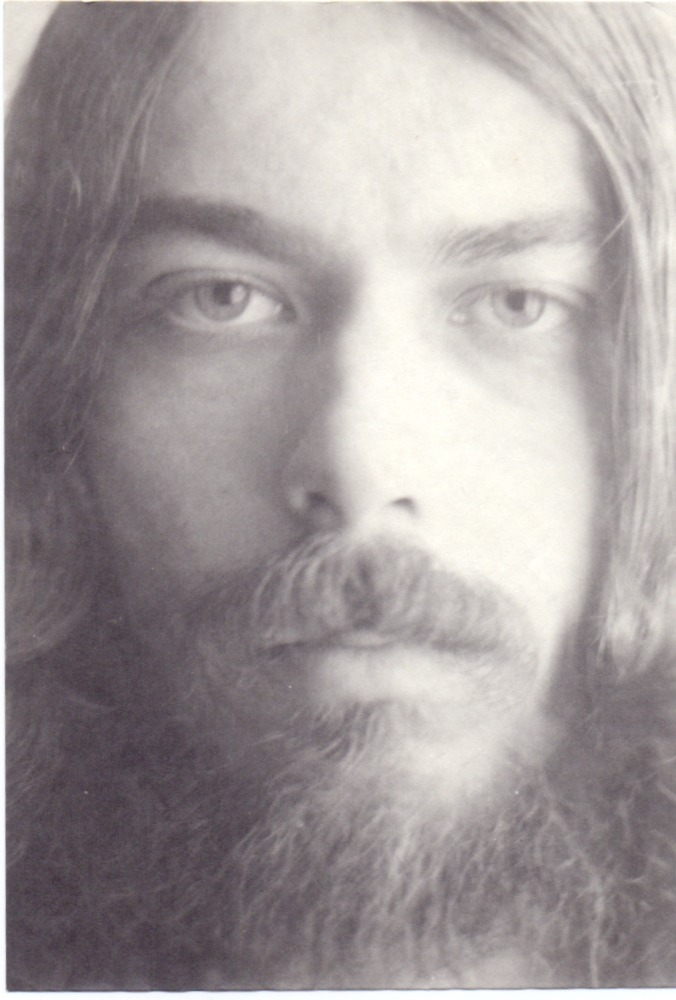

Tomáš Mazal was born on 22 March 1956 in Prague, Vinohrady. His father Jaromír Mazal was a bank clerk, his mother Jana Mazalová, née Havránková, a kindergarten teacher. He has a brother eight years older. As a teenager he experienced the invasion of the Warsaw Pact troops in 1968. When they invaded Czechoslovakia, he was far from his parents, in a camp in southern Bohemia. He was not interested in the high school he had entered through friends. So, in the early 1970s, the world of Prague‘s Old Town and Lesser Town pubs engulfed him. He came into contact with the so-called „longhairs“ or „máničky.“ Many now well-known authors and songwriters became his friends. He worked for a company that distributed and repaired both typewriters and copiers. Thanks to his job, he helped people whose typewriters had been slightly damaged during searches by State Security, which used this tactic to trace the origin of distributed texts. From the late 1970s, he started making independent films, writing his own books, contributing to samizdat periodicals, and founded an underground publishing house. He published not only his own books but also copied samizdat publications such as Opium for the People. His debut work was a biography of Jaroslav Hutka, and his films featured figures like Egon Bondy. With the regime change, he wanted to continue in publishing. He reached out to Bohumil Hrabal for a foreword to one of his books, which led to a friendship that lasted until Hrabal’s death. Until around 1992/93, Tomáš Mazal worked at the company Kancelářské stroje, which was undergoing turbulent privatization. He then took a position as a fire safety and occupational health specialist at the newly established firm Julius Meinl, where he remained until its exit from the Czech market in 2005. He later held a similar role at the successor chain Albert. He has remained in this field to this day (2024), with clients including Petřínská rozhledna. He lives in Prague (2024) and has two children.