Hereditary storyteller

Stáhnout obrázek

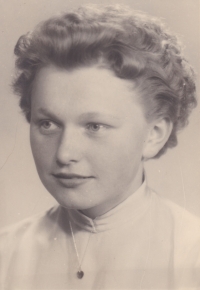

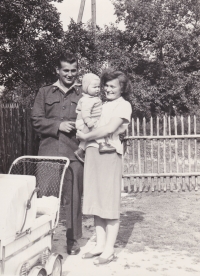

Vlastimila Málková, née Marková was born on the 17th of March of 1940 in Suchá at the foot of Železné Hory [Iron Mountains]. Both her parents had to walk to work to the Eckhardt factory in Chotěboř and Vlastimila was thus mostly cared for by her grandmother. Her grandfather František Kruml had fought in WWI where he sustained a gunshot wound during the fights and he liked to tell granddaughter stories about his wartime life. The witness tells about the end of WWII in her birthplace and about fear of the OUN-B (*) who kept hiding in forests around Spálava until the spring of 1947. In the 1950’s, the founding of Unified Agricultural Cooperative was planned. The Marek family were smallholders and they were forced to join the co-op by exchanging their field for others and by raising their production quota. Witness‘ husband Zdeněk Málek worked as a supply clerk in the Chotěboř engineering works. After he refused to join the Communist Party and disapproved of the invasion of the armies of the Warsaw Pact, he was fired and had problems finding another job. As a result, both their sons had problems getting the credentials to be admitted to high school. Nowadays, the witness is devoting her time to photography. At the time of the recording, she lived in Chotěboř. (*) Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists – Bandera faction