We knew that even if the evil was affecting us we had to resist it

Stáhnout obrázek

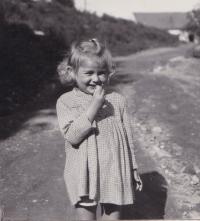

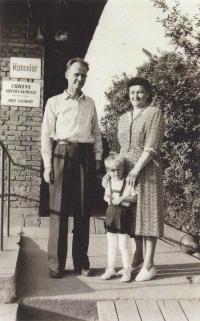

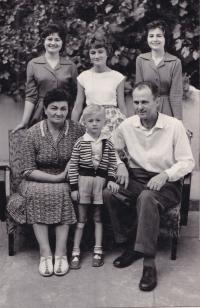

Marta Laudátová was born to Zdeněk and Marie Svobodas in Bosonohy near Brno on 13 April 1947. Her father was an active member of Orel, a catholic sports organisation, and was arrested and imprisoned along with others in Uherské Hradiště in January 1949. He was one of the people who were tortured with electricity. He was sentenced for high treason in the case Bohuslav Koukal et al. He served his sentence in a labour camp in Jáchymov. He came back in 1955 and was still on parole and under surveillance until 1962. The witness had three siblings. Apart from the youngest one they all faced difficulties being admitted to schools. She finished the primary school with excellent results but was only allowed to study to become a turner. Towards the end of her studies he got a chance to continue at a two-year high school, and she passed the school-leaving exam in 1967. She went on to study a high school of technology as a correspondence course. She married Zdeněk Laudát in April 1975. The couple has raised three children. She worked at the St Cyril-St Methodius Primary School in Brno after 1990. The witness is actively interested in the destinies of Orel members and political prisoners and revives the memory of the unjustly imprisoned.