In those days you couldn’t be sure who was who because they were often disguised. You couldn’t trust anyone.

Stáhnout obrázek

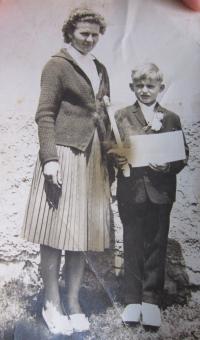

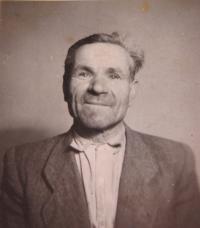

Anna Lašová, née Ligdová, was born in 1933 in the village Jelisavec (Jelisavac in Croatian) in Croatian Slavonia. Both of her parents were Slovaks and they left to Slavonia during the times of the Great Depression, just shortly before Anna‘s birth. Although the native village of Mrs. Lašová is located in Yugoslavia, its inhabitants used to be and still are predominantly Slovaks. In Jelisavec, Anna Lašová spent her childhood which was heavily affected by WWII. After the war, the family took the opportunity and re-emigrated to Czechoslovakia in 1949. They settled in the village of Martin pri Senci, which became the safe haven for a number of Slovak families also returning from Yugoslavia. Those re-emigrant families established one of the first collective farm (JZD/JRD) in Czechoslovakia. In the mid-fifties, Mrs. Anna married Vincent Láš, who spent his childhood in Slavonia as well (Mali Rastovac) and during the war fought in the Yugoslav partisan units. She moved with him to Nová Lublice near Opava, where they still live today.