The first time I saw Jan Kubiš was only when they showed me his severed head

Stáhnout obrázek

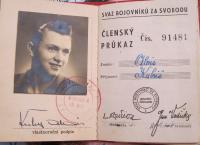

Alois Kubiš was born in 1932 in the village of Černá Hora. He is a distant relative of Jan Kubiš, who carried out the assassination on the German Reichsprotektor Reinhard Heydrich. In August 1942, when he was only ten years old, he was arrested together with his parents and sister. His parents were interned in the Little Fortress in Terezín and his sister was held in Prague. While in Prague, he was forced to identify Heydrich‘s assassins when he was shown their severed heads in glass containers. After this, he was briefly interned in Terezín and then for half a year in Masaryk‘s Institute in Prague, where Germans conducted tests with vaccines on him and other children. After the war he served in the army for several years. At present he lives in Šumperk.