I can‘t have anything to do with this regime

Stáhnout obrázek

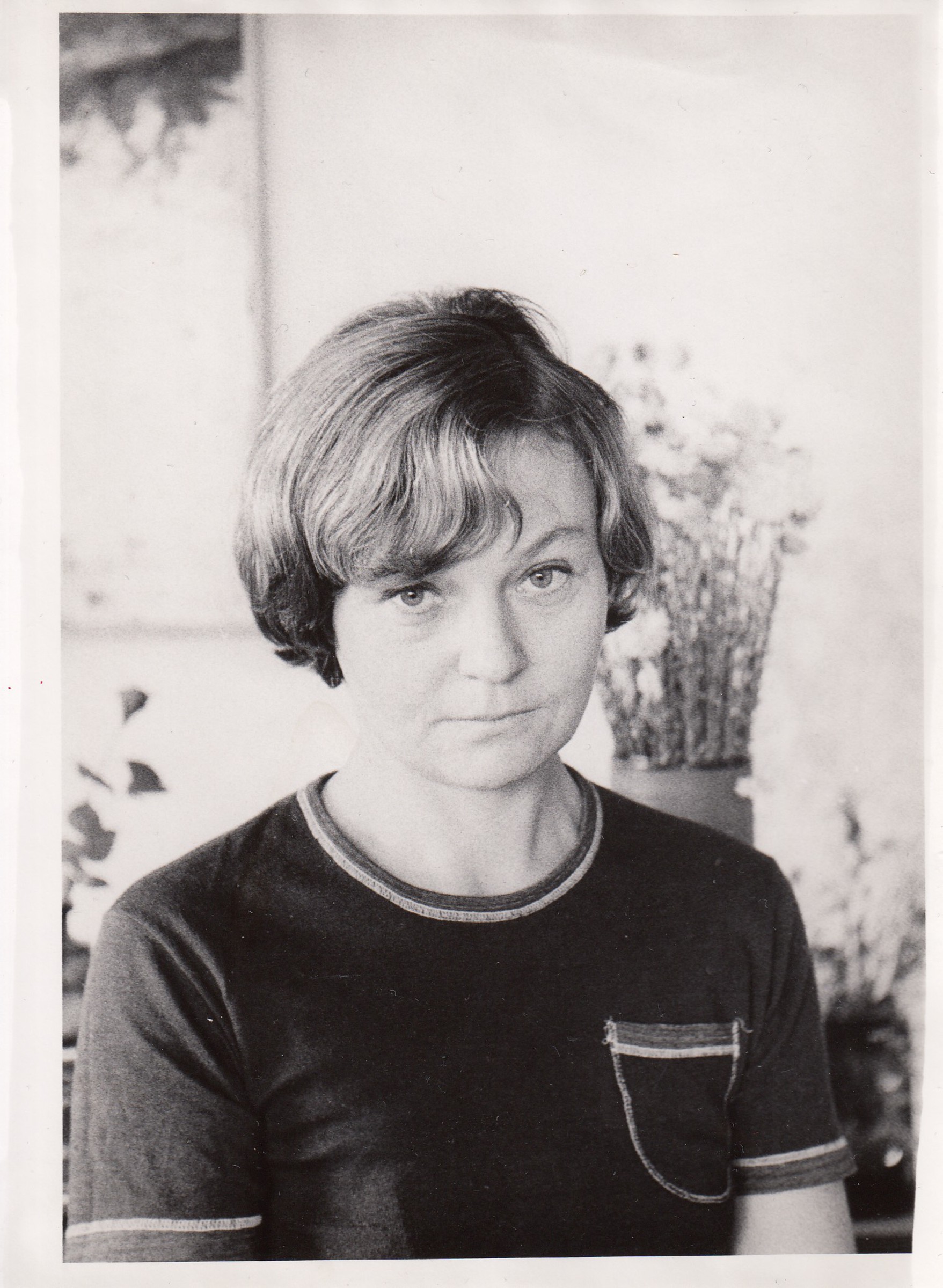

Eda Kriseová was born in 1940 in Prague and grew up in the very centre of the city, where her mother had a sculpture studio. During the war they had a shortage of food and moved to the countryside. After 1948, she had difficulties getting into university because of her cadre profile. Only after some time was she admitted to study journalism. In the 1960s she worked at the daily Mladá fronta (Youth Front) and later at Mladý svět (Youth World). In 1968 she went to Israel with a group of journalists and activists, where she learned about the occupation of Czechoslovakia. However, she was unable to connect with her home, where she had a husband and a young daughter. Eventually she managed to return home and subsequently began working with Ludvík Vaculík in Literary Lists. However, these were soon closed down by the normalisation authorities and the witness was banned from all activities. She began to write fiction in samizdat, became part of the dissent and volunteered in a sanatorium for the mentally ill. All this time she was monitored by State Security and regularly had to go to their interrogations. During the Velvet Revolution, she worked as a spokesperson for Václav Havel and after his election as president, she went with him to Prague Castle, where she first worked as a cultural advisor and later was put in charge of dealing with pardons and complaints about the injustices that the communist regime had inflicted on the people during the past forty years. After the revolution, she was also finally able to publish her books and lecture around the world.