I am a representative of the last generation of Breton language native speakers

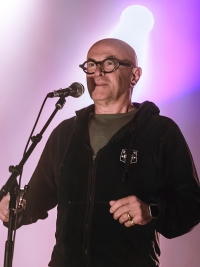

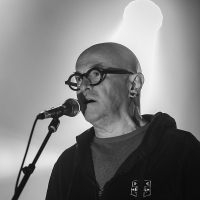

Stáhnout obrázek

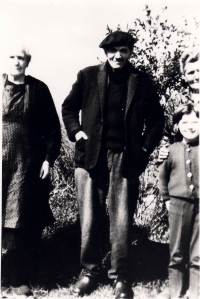

Yann-Fañch Kemener, a folklorist, a storyteller and a prominent traditional Breton music performer, was born on April 7th 1957 in Sainte-Tréphine, France. He was of humble origins. His father had been working as a wage labourer doing one-year contracts while his mother had been working as laundrywoman for most of the time. Thanks to his cousin, Eugèn Grenel, and Albert Boloré, his neighbour from a village, Yann-Fañch Kemener began to perform at a folk festivals estoù-noz and at the age of twenty he was already a celebrated traditional folk song performer. Encouraged by Albert Boloré and professor Léon Fleuriot, he also started to collect Breton folk verbal art which he studied extensively. In the early 80s, his promising performing career had been marred after his interview for the Le Gai Pied magazine in which he spoke openly about his homosexuality, unleashing a scandal in the conservative Breton society. In the following seven years, Kemener was banned from performing at the Celtic festival in Lorient. According to Hélène Hazer, a French journalist, Kemener‘s coming out resulted in overcoming the hypocritical stance towards the LGBT community in the Breton society and helped the acceptance of gay people in Brittany; Kemener‘s orientation also affected his artistic performance, giving it specific degree of depth and empathy. In the following decades, Kemener become one of the important persona of the Brittany‘s national revival. He published around thirty records and had also participated on several theatre projects. He did the gwerzioù, a traditional ballad genre, and the kan-ha-diskan, the Breton dance a chant style, but he also participated in musical experiments. In collaboration with Aldo Ripoche on cello and Florence Pavie on piano, he merged Breton chants with Baroque instrumental music; he is also known for his experiments with Didier Squiban employing jazz or orchestral music. Yann-Fañch Kemener performed in the Czech Republic several times on his tours from 2012 to 2016. The significant part of songs Yann-Fañch Kemener collected on his travels through Brittany was published in his book Carnets de route (Travel journals, 1996), he also published his region‘s oral stories in an anthology Collecte de contes en Basse-Bretagne (Collected stories form Lower Brittany, 2014). As an expert on folk verbal art collecting Yann-Fañch Kemener had been working at the University of West Brittany‘s Centre for Breton and Celtic Research. In 2009, he got the Order of the Ermine for his life long devotion to the culture of Brittany and was awarded the Order of Arts and Letters, Knight grade in 2015. Yann-Fañch Kemener passed away on March 16th 2019 in Tréméven, France.