The fellowship around the camp in Běleč has had an impact on my entire life

Stáhnout obrázek

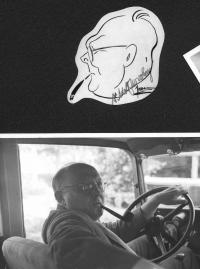

Marta Kellerová was born May 6, 1945 in Roudnice nad Labem. She grew up in Prague in the family of artist Jan Blahoslav Novotný. Her father owned a small advertising agency and later he cooperated especially with the ABC Theatre, and he was also an author of many actors‘ caricatures and posters, which he used to sign with the mark JEBENOF. Marta studied the Secondary School of Applied Art and in 1965 she began working in the Puppet Film Studio as an editing assistant. In 1966 she moved with her family to Kdyně, where her husband received placement as a pastor. The family lived there for five years and then they moved to the parish in Jimramov. In 1968 Marta‘s parents emigrated to Switzerland. After signing Charter 77, Marta and her husband were forced to leave the parish in Jimramov and move to Černošín in the border region. Later, the authorities cancelled Jan Keller‘s permission to serve as a pastor and he was even charged with disrupting the state control over churches. He had to earn his living as a worker in a saw-mill and as a boiler-operator. Although the charges were dropped after three years as unproven, his authorization for the ministry has not been renewed. With the help of Marta‘s mother, the family purchased a devastated house in Zbytov. After 1989, her husband was allowed to work as a pastor again, but he spent the first years of the democratic regime serving as a mayor in Jimramov. Marta Kellerová is the mother of four children. She and her husband live in Zbytov, where they organize various activities for young people, and she devotes her time to her original profession - creating wooden toys and puppets.