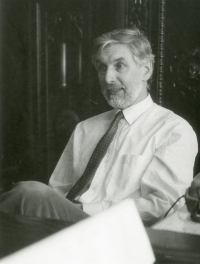

I‘ve always said what I think. I‘m surprised they didn‘t lock me up

Stáhnout obrázek

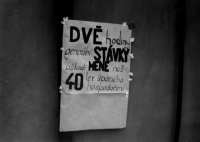

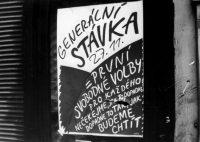

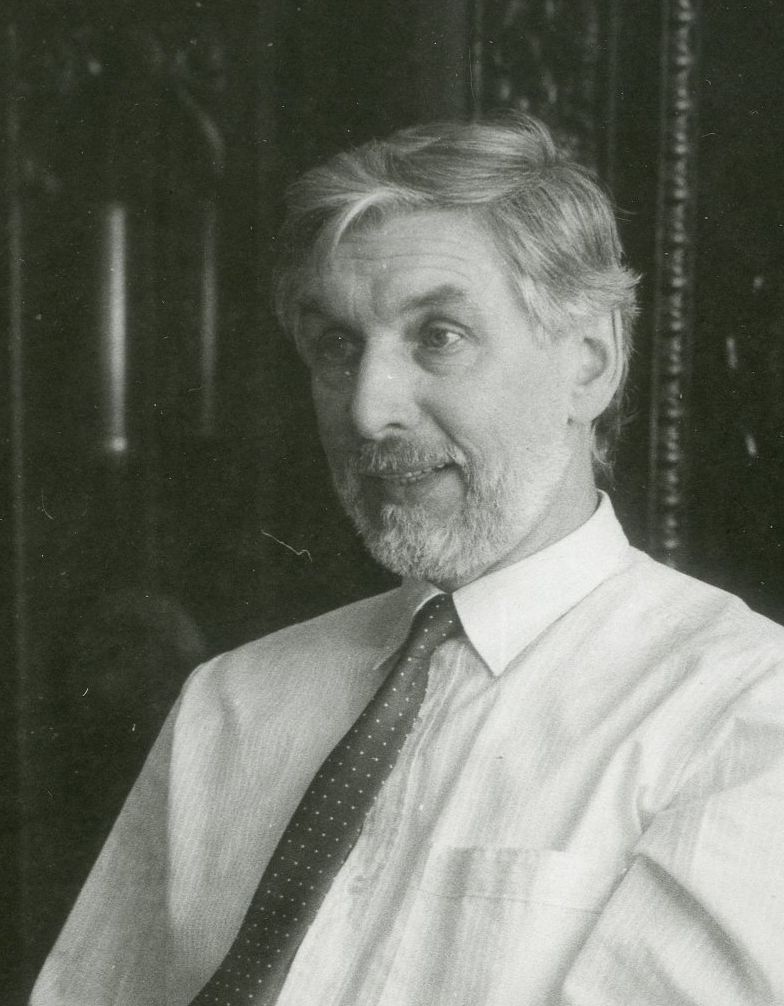

Miroslav Kalaš was born on 25 November 1933 in Strašnice, Prague, which became home to many Russian emigrants fleeing the „conveniences“ of the Great October Revolution, and witnessed their gradual deportation back to their homeland. As a curious boy with a thirst for adventure, he could not miss his participation in the Prague Uprising of 5 May 1945, during which he helped build barricades at the risk of his life. He spent the post-war period in his father‘s family home in Třemošnice near Benešov, most of which was taken over by Russian troops. He got to know their indiscriminate ways and his life hung in the balance again. After his burgher schooling, he studied at the Jan Masaryk Gymnasium and continued his studies at the Bishop‘s Gymnasium in Bohosudov, where in April 1950 he experienced Action K first-hand. He lent a helping hand to the interned religious, smuggled their letters to relatives and distributed them around Prague. In 1952 he graduated from the Žižkov Grammar School. However, his dream of studying medicine at university was not possible, and so he ended up working as a pig feeder in Jesenice. He escaped from this not very respectable job thanks to a course for medical laboratory technicians in Karlovy Vary, which he passed with honours, and then got a job in a laboratory in Planá near Mariánské Lázně. He then began his basic military service at the Czechoslovak Air Force NCO school in Zvolen and completed it at the Prague Defence Airfield in Milovice. He then returned to Planá, where he continued his work in the laboratory after the nuns left for their homeland. In 1958, he married a medical student from Plzeň, who came to the hospital to practice. By a tragicomic coincidence, their marriage was performed by a member of the State Security (StB), who had previously interrogated their two witnesses, both priests. Although he was never offered membership in the Communist Party, he was promoted to the position of head laboratory technician. In 1968, he gave a speech in the town square expressing his opposition to the occupation by Warsaw Pact troops. The following year, he placed black candles in the windows of the laboratory to commemorate the first anniversary of the occupation, after which he was dismissed from his post. When the fateful year of 1989 came, he actively participated in the restoration of the democratic state, among other things co-founding the Civic Forum. His career culminated in 1990 when he became the first democratically elected mayor of Planá.