They wanted him to fight the students in Pilsen with a machine gun. His girlfriend was among them.

Stáhnout obrázek

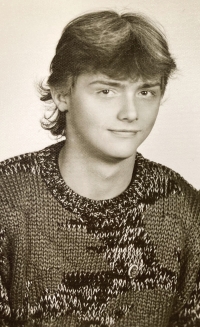

Zbyněk Jakš was born on 9 September 1969 in Bílina, Teplice region. After finishing the technical school of mining in Duchcov, he joined the Pluto Mine. He served his military service in Hranice na Moravě, where nuclear warheads were stored. In 1988 he participated in military exercises in the then Soviet Union, in the Karakum and Kyzylkum deserts. In November 1989 he was in the army worried that he would have to enlist with a gun in his hand in Pilsen, where his future wife was studying. After returning from the army, he continued working at the mine, where he changed in almost all mining positions. In 2000, he initiated a strike for better conditions for dismissed miners. The strike changed the legislation and helped a number of dismissed deep mine workers to cope with the new situation. In 2006, he became the director of the newly established Podkrušnohorské Technical Museum, which deals with mining history in the Most and Chomutov regions. At the time of filming in 2022, he still held this position and lived in Most.